Guests

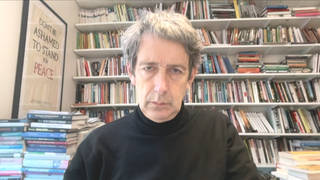

- Neve Gordonprofessor of human rights law at Queen Mary University of London and the vice president of the British Society for Middle East Studies.

As the world reels from the World Central Kitchen attack in which seven aid workers in Gaza were struck and killed by three separate Israeli missiles while delivering aid for starving Palestinians, we speak with prominent Israeli scholar Neve Gordon about Israel’s history of weaponizing food access in the Gaza Strip via the destruction of Palestinian agricultural land, labor restrictions and blockade, “controlling and managing the population through food insecurity.” Neve Gordon is a professor of human rights law and author of multiple books on Israel’s occupation of Palestine whose latest essay for The New York Review of Books is titled “The Road to Famine in Gaza.” Now as aid deliveries dry up amid fears of further attacks on humanitarian workers, Gordon emphasizes that “Israel has been controlling the food basket and using it as a weapon since the beginning of the occupation until today.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: A group of U.S. officials at USAID have privately warned the Biden administration that the spread of hunger and malnutrition in Gaza is, quote, “unprecedented in modern history” and that parts of Gaza are already experiencing famine. This comes as several aid groups are suspending work in Gaza after Israel killed seven aid workers with World Central Kitchen earlier this week. In a moment, we’ll speak to prominent law Israeli professor Neve Gordon about the famine in Gaza, but we begin with the words of two Palestinian mothers. This is Khuloud al-Masri, speaking at the al-Awda health center in Rafah, where her children are being treated.

KHULOUD AL-MASRI: [translated] I feel like my children will die in front of my eyes. What can I say? I don’t know what I am to do. I can feel them dying before my eyes. This is my daughter. It’s been five days she is without food or drink. I don’t know what to do for her. I am suffering. Sitting with my children, I am tired with them. It’s two of them, not just one. There’s not food or milk available. The girl is suffering from malnutrition. She is tired. The situation is so difficult. … I am tired. I swear, I am very tired. Their condition is very bad. My daughter is suffering in front of me, and I don’t know what to do for them. … I am unable to provide them with milk or Pampers or food. I don’t know what to do for them. The two of them are so unwell. This one, my daughter, has been like this for five or six days.

AMY GOODMAN: That was a Palestinian mother named Khuloud al-Masri. And this is another mother, named Reem al-Qadi, who spoke as she held her crying baby.

REEM AL-QADI: [translated] My daughter is ill, and she is suffering from malnutrition, and her blood is weak. We, of course, in the hospital are suffering from a catastrophic situation, a catastrophic health situation, very bad. There is no drinking water at all. The hospital is suffering and unable to provide water for us to give to our children. Our children have come here, not to get better and healthier, but their health situations have gotten worse. Most medications are not available. Healthy food is not available for our children. Healthy water is not available for our children. On one bed, they put three and four cases, which result in the children infecting each other and making their situations worse than before. … Of course, all of this is because of the Israeli occupation, the situation which we are in. They bombed hospitals. They tell us a hospital is a safe space. The hospital now is not a safe space. Most hospitals are no longer in service. All the sick are now being treated in one or two hospitals in the whole of the Gaza Strip. This is really a difficult situation. And we ask all countries, the world, to take our side and relieve us of the situation. It’s enough. Our children are dying in front of us, and we are unable to do anything for them.

AMY GOODMAN: That was a Palestinian mother named Reem al-Qadi, speaking at a hospital in Rafah.

We go now to London, where we’re joined by Neve Gordon, professor of international law and human rights at Queen Mary University of London, chair of the Committee on Academic Freedom for British Society of Middle East Studies. He’s the author of several books, including Israel’s Occupation, and co-author of Human Shields: A History of People in the Line of Fire. He’s co-editor of Torture: Human Rights, Medical Ethics and the Case of Israel. And he just wrote a piece in The New York Review of Books. It’s headlined “The Road to Famine in Gaza.”

Professor Gordon, thanks so much for being with us. Why don’t you take us on that journey? Tell us the antecedents to what we’re seeing today, the issue of famine in Gaza.

NEVE GORDON: So, perhaps I’ll begin with what we’re seeing, and then move back. We’re seeing destruction, and we’re seeing massive displacement, in an area that’s already food-insecure. And then we’re seeing Israel obstructing aid from entering Gaza. So, on average, in the past six months, 112 trucks have been entering per day, while before October 7th, 500 trucks were entering each day. We’re seeing consistent attacks on aid workers, as you mentioned in the previous item, with, on average, one aid worker being killed every day. And we’re seeing the destruction of one-third of the agricultural land in the Gaza Strip, 20% of the greenhouses and 70% of the fishing vessels in the Gaza Strip, so no internal food can be produced in the Gaza Strip. And as you mentioned earlier, what we’re witnessing, and what Reem and Khuloud have just expressed, is the most horrific situation a parent can experience, is their children dying in front of them of famine.

Now, what we wrote, Muna Haddad and me, is about the history of using food as a weapon in the Gaza Strip. So, if in 1967 Israel occupies the Gaza Strip, its approach is very different in the beginning. It surveys the Gaza Strip. It counts the agricultural land. It looks what the Palestinians are planting. And in the beginning, what it does is it actually plants trees and provides the Palestinians with better varieties of seeds, and it monitors the food basket of the Palestinians. And in its reports, it tells us that the food basket in 1966 was 2,400 calories per person, and after four years of occupation, it’s now 2,700, basically boasting about the improvement in the food basket. But what we see already then is that Israel is controlling the Palestinian food basket. And in the beginning, it wants to kind of increase the productive energies of the Palestinians so they can work in Israel as cheap laborers and extract their labor for Israel’s use.

Everything begins to change in the First Palestinian Intifada in December 1987, where Israel begins imposing restrictions on the Gaza Strip, first by creating magnetic cards that monitor the entrance of laborers into Israel and restricts the entrance of laborers to Israel. It also, a few years later, creates a fence and fences the Gaza Strip so that — and creates only four or five crossings. And later on, with the Second Intifada, we see a total reversal of the approach after 1967. We see Israel destroying agricultural land. We see it creating a buffer zone around the fence so that Palestinian farmers cannot get near the fence. We see it destroying fishing vessels. And see it limiting further the Palestinian food basket.

Then comes 2005, Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, the movement of its soldiers to the fence, the beginning use of the drones over the Gaza skies. And after Hamas wins in democratic elections in the Gaza Strip, we see the implementation of a blockade, where Israel basically blocks the Gaza Strip and monitors very carefully what enters and what exits. It further destroys more agricultural land. And then it creates — the Ministry of Defense, with the Ministry of Health, creates lists of items that can enter the Gaza Strip and items that cannot enter. So, flour and baby formula can enter, but chocolate and certain kinds of pastas cannot enter. And Israel begins to monitor the calorie intake of the population and creates what’s called — it called a “humanitarian minimum.” “We will allow,” Israel says, “a humanitarian minimum to aid to enter the Gaza Strip,” leaving the population regularly in a situation of food insecurity and controlling and managing the population through food insecurity. And every time there is a cycle of violence — and there’s been five major cycle of violence since 2008 until today — Israel closes off all of the borders, and what had been a food insecurity before the cycle of violence drops dramatically, and we see incidents of malnutrition and so forth.

And so, this is kind of the background of what we’ve been seeing. And when this war begins — so, we see that everything you’ve been describing earlier is intentional, because Israel has been controlling the food basket and using it as a weapon since the beginning of the occupation until today.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Professor Neve Gordon, you make the case in your article that — and this is perhaps one of the most surprising things — that Israel has made no attempt to conceal its policy of restricting food to Gaza. You cite Sara Roy’s earlier piece in The New York Review of Books, quoting her citation of a cable sent from the U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv to the secretary of state on November 3rd, 2008. The cable reads, “As part of their overall embargo plan against Gaza, Israeli officials have confirmed to [embassy officials] on multiple occasions that they intend to keep the Gazan economy on the brink of collapse without quite pushing it over the edge.” So, if you could elaborate on that and what you understand the justification of that to be, and why they were so — why they would be so disclosive about it to the Americans?

NEVE GORDON: So, what we see is we see a process from Oslo where Oslo was sold to the public as a peace process that will bring economic dividends for Israel and the Palestinians. And if you remember at the time, Gaza was described as the new Singapore, and we will make Gaza thrive, and there will be a Singapore in the Middle East.

Now, what we see in the years immediately after the Oslo Accords were signed, that, indeed, Israel was enjoying the economic dividends in the Gaza — from the Oslo Accords, but the Palestinians, both in the West Bank and in Gaza, and particularly in Gaza, the economic situation drops because Israel is basically strangling the Palestinian economy. And if you mention Sara Roy, then I will use her concept of de-development. Israel de-develops the Gaza Strip, destroying the agricultural land, destroying the factories.

And it is not shy in doing so. It is basically asserting its control and letting the Palestinians in Gaza know who is the lord of the land, and letting the American counterparts also know who is the lord of the land. And through this, we see a situation where the economics — the major reason for the food insecurity in the Gaza Strip before this war was indeed the blockade. But the blockade, what it does, it strangles the Gaza Strip economically. So, a year before the war, we have a GDP per capita in the Gaza Strip of about $1,000 per person, while in Israel it’s $52,000. An hour away — this is before the war. An hour away from my apartment in Be’er Sheva, where I used to live, and Gaza Strip, that’s the distance between the two regions, yet in the Gaza Strip a newborn is seven times more likely to die than in Be’er Sheva, because the social detriments of health, because the economic strangulation, because of the lack of healthcare and so forth.

And the message was clear from the beginning: “We control you. If you do not bow down, then we will hit you harder.” And that’s what Israel has been doing for years in the Gaza Strip. And that’s what it’s been — and the Americans have been watching. Americans have been seeing this happen. And the Americans have not said anything to Israel in this sense and not stopped Israel’s actions. And then we have October 7th, and we’ve seen what’s happened since then.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Professor Neve Gordon, we have to break here, but we want to ask you to stay after the show so we can continue this conversation, and we’ll post it online at democracynow.org. Professor Gordon teaches international law and human rights at Queen Mary University of London. We’ll link to your piece in The New York Review of Books headlined “The Road to Famine in Gaza.”

Next up, we go to Senegal, where a pair of opposition leaders went from prison to the presidency and the prime ministership in three weeks. Stay with us.

Media Options