Topics

Guests

- Raoul Peckacclaimed Haitian filmmaker and the director of the new film Orwell: 2+2=5.

- Alex GibneyAcademy Award-winning director and producer of the new documentary releasing Friday titled Orwell: 2+2=5.

Links

We speak with the acclaimed filmmakers Raoul Peck and Alex Gibney about their latest documentary, Orwell: 2+2=5, which explores the life and career of George Orwell and why his political writing remains relevant today.

“We are living again and again — not only in the United States, but in many other countries, including in Europe, in Latin America, in Africa — the same playbook playing again and again,” says Peck, who directed the film.

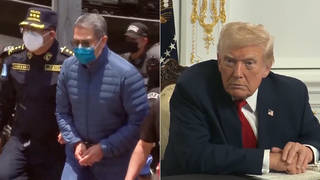

Gibney, a producer on the film, says Donald Trump perfectly illustrates the “assault on common sense” that is part of any authoritarian system. “What you instinctively know to be true is upended by the authoritarian leader, so that everything flows from him,” says Gibney. “He just invents things on the spot, but he expects them to be revered as true.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: In the days after President Donald Trump took office in 2017 during his first term, George Orwell’s 1984 came a best-seller in the U.S. The classic 1949 dystopian work introduced the world to the terms “Big Brother,” “thought police,” “newspeak” and “doublethink.” Orwell wrote 1984 as a cautionary tale more than 75 years ago, and some say it has even greater relevance now in Trump’s second term and around the world.

Now a new film by the Oscar-nominated director Raoul Peck is opening Friday in theaters, that explores the life and legacy of George Orwell. It’s called Orwell: 2+2=5. This is the trailer.

GEORGE ORWELL: [voiced by Damian Lewis] When I sit down to write a book, I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose.

O’CONNOR: [played by Michael Redgrave] Again, how many fingers?

GEORGE ORWELL: My starting point is always a feeling of injustice. The very concept of objective truth is fading out of this world.

WINSTON SMITH: [played by Edmond O’Brien] I’m going to set down what I dare not say aloud to anyone.

GEORGE ORWELL: This prospect frightens me much more than bombs. The words “democracy,” “freedom,” “justice” have, each of them, several different meanings, which cannot be reconciled with one another. Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: The love in the air, I’ve never seen anything like it.

GEORGE ORWELL: And murder respectable. Freedom is slavery. War is peace. Ignorance is strength. Totalitarianism, if not fought against, could triumph anywhere. Do you begin to see, then, what kind of world we are creating?

NERMEEN SHAIKH: That’s the trailer for the new film, Orwell: 2+2=5. And this is a clip that features the voices of President George W. Bush’s Secretary of State General Colin Powell and Russian President Vladimir Putin. It begins with the words of Orwell as read in a 1956 British film adaptation of his novel 1984.

BIG BROTHER: [voiced by John Vernon] We’re at war with the people of Eurasia, the vile and ruthless aggressors who have committed countless atrocities and who are guilty of every bestial crime a human being can commit. They’ve laid waster our land, destroyed our factories, looted our homes, massacred our children and raped our women!

SECRETARY OF STATE COLIN POWELL: When Iraq finally admitted having these weapons in 1995, the quantities were vast. Less than a teaspoon of dry anthrax, a little bit, about this amount, this is just about…

GEORGE ORWELL: [voiced by Damian Lewis] This kind of thing happens everywhere. But it is clearly likelier to lead to outright falsification in societies where only one opinion is permissible at any given moment.

PRESIDENT VLADIMIR PUTIN: [translated] I’ve made the decision to conduct a special military operation. Its aim will be to protect those who have been persecuted in the Kyiv region’s genocide these past eight years. Our goal, therefore, will be to demilitarize and de-Nazify Ukraine.

GEORGE ORWELL: The organized lying practiced by totalitarian states is not, as is sometimes claimed, a temporary expedient of the same nature as military deception. It is something integral to totalitarianism, something that would still continue even if concentration camps and secret police forces had ceased to be necessary. Totalitarianism demands, in fact, the continuous alteration of the past, and in the long run probably demands a disbelief in the very existence of objective truth.

VICTOR OTTO: [translated] Had we not engaged in our special military operation, they would have attacked Russia. They, the Nazis, had long been preparing an attack.

O’BRIEN: [played by Lorne Greene] How many fingers am I holding up, Winston?

WINSTON SMITH: [played by Eddie Albert] Four.

O’BRIEN: And if Big Brother were to say not four, but five, then how many?

WINSTON SMITH: Four.

O’BRIEN: How many fingers, Winston?

WINSTON SMITH: Stop it. Anything. Five.

O’BRIEN: No, no, Winston.

WINSTON SMITH: Stop the pain!

O’BRIEN: Winston, that is no use. You are lying. You still think you see four.

WINSTON SMITH: How can I help, when it’s — five!

O’BRIEN: Two and two do not always make four, Winston. Sometimes they make five. Again, how many fingers am I holding up?

AMY GOODMAN: That’s a clip from the new documentary Orwell: 2+2=5. That last part is from a 1953 film adaptation of Orwell’s novel 1984.

For more, we are joined by Academy Award-winning director Alex Gibney, producer of Orwell: 2+2=5, and by the film’s director, Raoul Peck, the acclaimed Haitian filmmaker. His past films include Exterminate All the Brutes, I Am Not Your Negro — that’s one of my favorite documentaries of all time — The Young Karl Marx, Lumumba: Death of a Prophet and Haiti: The Silence of the Dogs. Raoul Peck served as Haiti’s culture minister in the 1990s.

We welcome you both back to Democracy Now! Raoul, talk about the origins of this film, why you decided to make this.

RAOUL PECK: Well, Alex is better to answer that first question. You want to tell it?

ALEX GIBNEY: Well, no, I got a call from a man who had assembled all the rights to Orwell’s works and wondered if I wanted to executive produce it. I said, “Yes, on one condition: if we can get Raoul Peck to direct it.” And so, I turned to Raoul. And luckily, he answered my call and said yes. So, that’s how it started. But it also seemed like a film — I mean, it began some years ago. It was like two or three years ago we started on this project. It was relevant then. We had no idea how relevant it was to become.

RAOUL PECK: Yeah, and I remember when we start working on it. For me, Kamala Harris was going to be president, so — and despite that, I knew that this country and many other countries around the world needed Orwell to come back and — because he had been one of the incredibly analyzer of how a totalitarian regime, but also any type of abuse of power function. You know, he teached how the signs — how to recognize the signs. And, you know, coming from Haiti as a young man and young boy, I also recognize the signs — you know, the attack on the press, the attack on justice, the attack on academia, the attack on any institution that can be a bulwark against totalitarian. And we are living again and again — not only in the United States, but in many other countries, including in Europe, in Latin America, in Africa — the same playbook playing again and again.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So, Raoul, you’ve said in another interview, “I don’t make biographies. I choose a moment in the life of a character that allows me to tell the bigger story. For Orwell, I found that moment quite rapidly.” So, if you could elaborate on that? So, Alex comes to you with the idea of this film, and what do you think of Orwell?

RAOUL PECK: An idea to which I say “yes” immediately. I don’t know why, but that happened. But you’re not offered every day to be able to immerse yourself in the whole body of work of an author that that you revere and that is important, like James Baldwin was important for me, too. But I know that before going, plunging into it, I had to find a story. I had to find — indeed, I don’t do biography. I try to find a story with a character, with emotions, with contradictions, and a story that allows you to see a film multiple times, not just for what is happening now currently, but also that you can watch in 30 years, and you will learn as much.

So, the story for me was Orwell in the last year of his life, where he’s struggling to finish 1984. And he will finally finish it, but will die four months later. And he’s only 49. So, the drama of that, you know, and the struggle to finish that, you know, for an author, I thought, was — would give me the fine line of the story and allow me to revisit all his body of work.

AMY GOODMAN: Writing through dealing with tuberculosis before he died. But for especially the younger generation, who he was, why he came to have this view, this warning to the world about totalitarianism, authoritarianism?

RAOUL PECK: Well, because it’s — you know, people have thought, including myself, you know, reading Orwell when I was young, always thought of him of a sort of dystopian and science fiction author. But in fact, he was writing about things that he went through in his life, being born in India, and that’s why I use that photo of Orwell as a baby in the hand of a Black nanny. And then he went to Myanmar today, you know.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Burma, yeah.

RAOUL PECK: Burma at the time, which was a British colony. And he went there as a 19-year-old, as a soldier there, and he realized the price of colonialism. He was himself the bully. He was on the wrong side. And that experience, I think, shaped his whole thinking. And he wrote about it in a very candid and open way and self-critical way.

And then the Spanish War, again, as a young man in his thirties, to volunteer to fight with the republic against the putschists, Franco, etc. So, all those moments shaped his mind. And, you know, there is a phrase where he said, you know, “After the Spanish Civil War, I knew where I stand.” And that was the turning point for him and of — as well, for the film, to establish who he actually was, and his whole writing, saying that “I want to — you know, to write about politics and art together.” It was never a contradiction for him.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And indeed, he said the decision not to make art about politics is itself a political decision —

RAOUL PECK: Of course.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: — which you —

RAOUL PECK: Yeah, and, as he said, neutrality cannot be — is also a political position. You know, you can’t be neutral. Neutral of what? You know.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: But the other — you talked a little bit about his time in — he was born in India, but I think he was just a few months old when his mother brought him back to England. But then he spends, as you said, from 1922 to '27, five years working as a policeman in, at the time, British-colonized Burma. And as a policeman, he says that he was part of the actual machinery of despotism, and as a result of which — another quote from the film — that he operates, quote, “on a simple theory that the oppressed are always right and the oppressors wrong: a mistaken theory, but the direct result of being one of the oppressors yourself.” So, if you could talk about that? And then, also we'll get into, you know, the extent to which, of course, this experience with colonialism, a direct one, as one of the colonizers, but then also the question of class. Throughout the film, he explains his own formation by his position, as he calls it, being lower-upper-middle class.

RAOUL PECK: Yes. Well, the first part of the question, you know, I have — I had a very good friend, the writer Russell Banks, and we had had that discussion many times. And he said the real story of racism in America can only be told by somebody who was a member of the Klan. And it’s a little bit the same way. If you have been in the belly of the beast, you have learned how the beasts think. You have no — you know all the instruments. You know how they function, etc. And that’s what Orwell was able to do. You know, he was doing things that he would come to regret, but he knew them intimately. And about the second part of your question, I forgot. It’s about —

NERMEEN SHAIKH: About class.

RAOUL PECK: About class. You know, that’s — I was thinking recently about how every politician in this country is using prominently the middle class, as if it’s like something — you have the middle class, and then you have the very rich and the very poor. And so, every citizen wants to be in that middle class. But it’s a way also to erase all class distinction, all the nuance of being in one or the other, is to erasing the working class, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to a clip, again, from your film, Orwell: 2+2=5.

GEORGE ORWELL: [voiced by Damian Lewis] I do not think one can assess a writer’s motives without knowing something of his early development. His subject matter will be determined by the age he lives in. At least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own.

When I was not yet 20, I went to Burma in the Indian Imperial Police. In an outpost of empire like Burma, the class question appeared at first sight to have been shelved. Most of the white men in Burma were not of the type who in England would be called “gentlemen.” But they were “white men,” in contradistinction to the other and inferior class, the “natives.”

In the free air of England, that kind of thing is not fully intelligible. In order to hate imperialism, you have got to be part of it. But it is not possible to be part of such a system without recognizing it as an unjustifiable tyranny. Even the thickest-skinned Anglo-Indian is aware of this. Every “native” face he sees in the street brings home to him his monstrous intrusion. But I was in the police, which is to say that I was part of the actual machinery of despotism.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So, that’s a clip from Orwell: 2+2=5. And there, we hear about Orwell’s experience with colonialism and how that shaped his ideological formation, so — which Raoul just talked about. So, Alex, I’d like you to talk a little bit about, you know, a comment that — an Orwell quote that’s also in the film, the fact that leaders can claim that something that happened didn’t happen, or that two and two is five. This fact scares me “more than bombs,” and this is not a “frivolous statement.” So, if you could elaborate on the significance of and the importance of this in our present moment?

ALEX GIBNEY: Well, I think that what Orwell was talking about was the idea of authoritarian leaders’ assault on common sense. In other words, what you instinctively know to be true is upended by the authoritarian leader, so that everything flows from him — usually “him.” And that’s the — that’s what we’re experiencing in this moment. We have a president who you can’t even say that he’s a liar, because he just invents things on the spot, but he expects them to be revered as true. Two plus two equals five. That is the the effective —

RAOUL PECK: Slogan.

ALEX GIBNEY: Well, it’s a slogan, but that’s how he impresses us with his power, that he can make us rudder against our own common sense. That is — and that’s the danger we must all, you know, rise up against. That’s the problem at this moment.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And also, he makes — I mean, the point that also you have in the film, Orwell saying, “To be corrupted by totalitarianism, one does not have to live in a totalitarian country.”

ALEX GIBNEY: Right. And I think also — you know, the other thing to remember, I think, that’s important here is that what we’re living through in this country is not unique, and it’s kind of a playbook that authoritarian leaders go through throughout the world. But also, you know, one of the geniuses — one of the things that’s great about Raoul’s film is that there’s a juxtaposition of present and past, and also country to country, and you can see these same patterns emerge over and over and over again. And it’s a kind of a simple playbook to make us all believe that two plus two equals five, or at least to assert that the — that’s the pledge of allegiance, “two plus two equals five.” But it’s not unique to Donald Trump. And I think that it’s one of the great triumphs of the film.

AMY GOODMAN: Raoul Peck, you told Variety, “We are in the hands of a bunch of crazy people who have an agenda totally written out in Project 2025, the same way that Hitler wrote Mein Kampf.” And you also — I mean, just talking about Orwell saying, “Totalitarianism demands, in fact, the continuous alteration of the past, and in the long run probably demands a disbelief in the very existence of objective truth.”

RAOUL PECK: Well, exactly. And I think everybody remembers when Ms. Conway came with the phrase “alternative facts,” you know, and everybody started laughing about that. But that was what we call the beginning of newspeak, you know, and where you’re actually saying one thing and doing the contrary, the same when Netanyahu at the U.N. said Israel wants peace, while they are bombarding Gaza. So, the absurdity and the contradiction of this is — have invaded our lives. And I know, as — again, coming from Haiti, I remember as a young boy hearing Kennedy and other presidents talking about democracy. And at the same time, they were financing and supporting the dictatorship in my country, or in Congo supporting Mobutu, when we were there, and at the same time talking about peace, talking about the good thing that democracy was bringing. So, that double language have always existed for the imperialist countries and colonialism. You know, there is the talk, and there is the reality. And Orwell, if we can learn something from him, is that he wrote about the reality, not some dystopian future, you know. And we can relate to that, and we can understand how this machine functions.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And so, Raoul, you mentioned newspeak. And in the film, you give several examples from the contemporary moment: “special military operation,” which includes — which equals “invasion of Ukraine”; “vocational training center,” which equals “concentration camp,” a reference to the Uyghurs in China; “legal use of force,” “police brutality”; “antisemitism,” 2024, equals “weaponized term to silence critics of the Israeli military.” Now, if you could talk about, in particular — because you do include it in the film — the proliferation of these terms through a totally new form, social media?

RAOUL PECK: Absolutely. It multiplied that by the million. And we are being bombarded by so-called information, which are absolutely not information. And there is no checking about that. And there is this sequence with Ocasio-Cortez, as well, criticizing or asking Zuckerberg, you know: What is his fact-checking department doing on Facebook? So, it’s such an enormous problem. Like, Orwell tells us that at the moment where you cannot trust language anymore, you’re not in a democracy.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you leave this film more hopeful or less?

RAOUL PECK: Well, it’s — “hopeful” is not a word I can function with. For me, it’s about what do you do once you see that something is not functioning. And I think about what response should we make, what alliance should —

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And what is the response?

RAOUL PECK: Yes, well, that will be the responsibility of each one of us, you know, wherever we are, journalists, as well politicians, but also the civil society. The response, you know, like Orwell said, 84% of Oceania, you know, they are the one who has — or, he calls them the proles, and they are the one who has to bring a response, like the civil rights movement. You know, it was a coalition of very different people, very different movements, and they succeeded in changing this country.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I encourage everyone to see this film. It’s at IFC, opening tomorrow night here in New York, and then moving on to Los Angeles and then to the rest of the country. Raoul Peck, director of Orwell: 2+2=5. Alex Gibney produced the film. Thank you so much, both, for being with us.

Next up, a look at life in El Salvador under a total abortion ban with the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Maria Hinojosa. Stay with us.

Media Options