More than a dozen West African men who were deported to Ghana by the United States have since been returned to their home countries by the Ghanaian government, despite legitimate fears of torture or persecution at home. Ghana is one of a growing list of countries that have signed “third country agreements” with the United States to accept U.S. deportees. Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project, notes that in many cases judges have ordered the Trump administration not to deport immigrants to countries where they may face persecution. “It’s a complete ruse to get around the order from the immigration judge,” he says. “This fits a pattern of the Trump administration trying to evade court orders.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We continue now on the subject of immigration and turn to the case of a group of West African men who were granted protection from deportation to their home countries on account of legitimate fears of persecution or torture at home, so the Trump administration instead sent them to Ghana. Ghana is one of a growing list of countries that have signed third country agreements with the U.S. to accept deportees from other countries. This is the president of Ghana, John Dramani Mahama, speaking earlier this month.

PRESIDENT JOHN DRAMANI MAHAMA: We were approached by the U.S. to accept third-party nationals who were being removed from the U.S. And we agreed with them that West African nationals, you know, were acceptable, because all our fellow West Africans don’t need a visa to come to our country. So, if they decided to travel from U.S. to Accra, they don’t need a visa anyway. So, if you are bringing our colleague West Africans back, I mean, that’s OK. And so, I think that agreement has been activated, and a first batch of 14 nationals came.

AMY GOODMAN: But it appears the deportees did not stay in Ghana for long. Upon arrival, they were detained, and within days, it appears, Ghanaian officials began repatriating the men to their home countries — exactly where they feared going.

In the lawsuit filed by Asian Americans Advancing Justice and joined by the ACLU, attorneys assert the U.S. sent the men to Ghana with full knowledge they would then be sent to their home countries. U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan said she was “alarmed and dismayed” at the men’s removals, and that they, quote, “appear to be part of a pattern and widespread effort to evade the government’s legal obligations by doing indirectly what it cannot do directly,” unquote. But she said her hands are tied.

For more, we’re joined by Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project, also adjunct professor at Columbia Law School, on the team representing some of the people sent to Ghana. In recent weeks, Lee won a major case in which one of the most conservative, if not the most conservative, federal appeals court panel in the country ruled President Trump cannot use the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to speed the deportations of people his administration accuses of membership in a Venezuelan gang.

Lee, welcome back to Democracy Now! Talk about this case of the men being sent to Ghana, with the U.S. fully knowing that Ghana will then send them exactly where they fear, where they fled from, their home countries.

LEE GELERNT: Yeah, thanks, Amy. And you’ve described it perfectly.

I think, and unfortunately, this fits a pattern of the Trump administration trying to evade court orders. So, what’s happened is, these individuals have gone to immigration court, and the immigration court has said, “You can be removed from the United States, but you cannot be removed to your home country, because it’s more likely than not you’ll be persecuted or tortured there.” So the United States government knows they can’t send these individuals to their home country. They’re prohibited by an immigration court from doing so.

So, what we think they’re doing is finding third countries — and Ghana may just be the tip of the iceberg — sending them to the third country, like Ghana, knowing full well — and we actually think directing the third country, in this case, Ghana, to send them on to their home countries. So, it’s a complete ruse to get around the order from the immigration judge. The United States government, at a minimum, knows very well that the third country is going to send them on to persecution or torture — and again, we think, probably directing them.

And as you said, Judge Chutkan felt her hands were tied, because they were already on the move. So, what that suggests is that we’re going to need to potentially bring a lawsuit for people still in the United States to stop the policy prospectively. So we are trying to get our hands around exactly what’s going on. Obviously, the United States government is not playing this out in public, so we’re going to have to do some digging. But it’s becoming more and more clear that this is the United States government’s way of sending people to persecution and torture, using these third countries to shield what they’re doing.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Lee, could you explain how these third country agreements came about in the first place? Was there anything like this prior to the Trump administration or in his previous one?

LEE GELERNT: Yeah, that’s a very good question. So, there’s always been what’s called diplomatic assurances, but they’ve been used very sparingly and only on an individual basis. So, there are times when an individual can’t be sent to their home country. The United States finds a third country to take them, but adopts a diplomatic assurance with that country that they will not be persecuted or tortured there. And because it was done so rarely and only with individuals, it could be monitored much more carefully. Are there safeguards in place to make sure this particular individual will be safe in this third country?

What the Trump administration has done now is said, “We’re going to do these categorically. We’re going to get countries — we’re going to pressure countries into taking as many people as we can send there and claim that they’ll all be safe there.” So, we don’t think that the individuals will all be safe in the third country. But what’s happening now with Ghana is a whole 'nother chapter of this. Not only are they sending dozens and dozens of people to third countries under the claim that they'll be safe there, but now they’re having these third countries send them on to countries where it’s clear they won’t be safe, because an immigration judge has already found they won’t be safe.

AMY GOODMAN: Lee —

LEE GELERNT: So, the third — yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s turn to a declaration by a plaintiff who goes by the pseudonym “K.S.,” out of concerns for his safety. He made the declaration —

LEE GELERNT: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: — while in hiding in the Gambia. The declaration reads, in part, quote, “On March 7, 2025, I won deferral of removal under the Convention Against Torture from my home country of The Gambia due to the specific risks of torture and death I face there on account of my sexuality. … I spoke repeatedly with two Ghanaian immigration officials, named Ibrahim Lang-Hani and A. Aman [phon]. I explained to them my fear of returning to the Gambia, the basis of my fear, and the fact that I’d won protection from being returned to The Gambia under the Convention Against Torture. I told them I wanted to stay in Ghana for my safety. The official Ibrahim just told me that my final destination was The Gambia, based on orders from ICE officials and his Ghanaian superiors. … I am now living in hiding [in the Gambia] with the help of my sister. I am seeking a way out of the country as soon as possible for the sake of my life.” Do you know K.S.?

LEE GELERNT: Well, he’s one of the plaintiffs in the case. I can’t reveal, obviously, where he is or, I mean, specifically or exactly what’s going on, for safety. But I think his case is a prime example of what the United States is doing.

So, when we went before the judge, the government repeatedly said, “Well, we’re sending people to Ghana, but they’ll be safe there.” And we pointed to K.S. and said, “But you know K.S. now. We have told you Ghana — has been sent on to the very country an immigration judge said he cannot be sent to because he’d be in danger of torture there.” And the United States government said, “Well, we have a diplomatic assurance with Ghana that that won’t happen.” And we said, ” But it has happened.” And they kept saying, “Well, the court can’t do anything.” And so, what I finally said, out of exasperation, is: “Why aren’t you concerned? You claim you have a diplomatic assurance with Ghana not to send people on to torture. If you really have that, why aren’t you concerned? Why do you need a court order to call Ghana and say, ’You’re violating this diplomatic assurance’?”

Well, of course, the Trump administration remained silent, didn’t say anything. But the United States government should, presumably, be just as concerned as we are if Ghana is breaking the agreement. The truth is, Ghana is not breaking the agreement. The truth is, the United States has told Ghana to send these people on to their home countries.

AMY GOODMAN: Lee, can you talk about the Trump administration trying to send Kilmar Abrego Garcia to Eswatini, formerly Swaziland, I mean, already having sent him to El Salvador to the mega-prison CECOT, then one of the lawyers admitting that they were wrong, and they eventually brought him back, now deporting him to Africa —

LEE GELERNT: Right. I mean, so —

AMY GOODMAN: — where he has no ties?

LEE GELERNT: Yeah, so, this is a situation where the United States government is intent on putting him in a bad situation. You know, they admitted candidly — at least one lawyer, who’s now been fired, has candidly admitted it was a mistake. Rather than admitting that mistake, the Trump administration keeps doubling down and doubling down, and now is going to send him to a country which he has no ties. But you know that his case has gotten a lot of publicity because of that mistake, but it’s part of a pattern where right now the United States government is sending people all over the world to places they have absolutely no ties to. And so, this is a remarkable break from prior administrations, both Democratic and Republican.

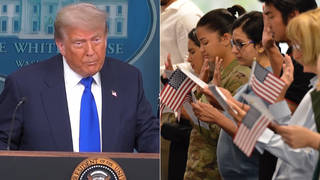

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So, let’s go to Trump’s words, in fact, talking about asylum seekers just earlier this week at the opening of the U.N. General Assembly.

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: When your prisons are filled with so-called asylum seekers who repaid kindness — and that’s what they did: They repaid kindness with crime — it’s time to end the failed experiment of open borders. You have to end it now. Let’s see, I can tell you. I’m really good at this stuff. Your countries are going to hell.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So, that’s Trump speaking earlier this week at the U.N. General Assembly opening in New York. So, Lee, your response to that? And, of course, what he said is not new. He’s repeated it multiple times, and also said that he’s going after the worst of the worst.

LEE GELERNT: Yeah, so, two things about that. One is, I think when people said they wanted more immigration enforcement, they were voting for an abstraction, sort of a vague abstraction. Now that people are seeing what’s happening in practice, I think you’re seeing pushback, because it’s very clear he’s not just going after the worst of the worst. The administration is consistently seeking to arrest, detain and deport people who have no crimes whatsoever, families who have lived here for decades, who have paid taxes, are working, maybe their children are U.S. citizens. So, that’s absolutely clear that notwithstanding the administration’s constant refrain that they’re only going after the worst of the worst, that’s not true.

But let me also talk about specifically asylum, because I think what’s gone underreported is the fact that right in the beginning of the administration, he claimed that migrants were, quote-unquote, “invading” the United States, and he ended all asylum. So, people say to me, “Well, doesn’t the border need some fixing?” And we are all in favor of revision to border policy if it can be reasonable and have due process. What I don’t think people understand is that the Trump administration has tried to eliminate all asylum by any means. So, that means you come here; even if you present lawfully at a port, even if you have absolutely overwhelming evidence you will be persecuted on account of your religion or your political opinion, there is no way in the United States any longer to apply for asylum. That puts us in a small handful of countries — Iran, North Korea — that don’t have an asylum system. It’s a remarkable turn of events for the United States, after we made the solemn promise after World War II we would never send people back to danger without even a screening.

People are constantly saying me, “Well, didn’t the border — you know, the asylum process need streamlining?” Fine, but I don’t think people realize there is zero pathway for people in danger now to apply for asylum in the United States. That’s an extraordinary turn of events. We have challenged it. We won in court so far. The government has appealed. I suspect that it will go to the Supreme Court. But people need to keep an eye on that, because it’s simply not true that there’s a way to apply for asylum any longer. You’re in danger; the United States no longer gives you a safe haven, no matter how much danger you’re in.

AMY GOODMAN: Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project, thank you so much for being with us.

When we come back, we get an update on the Gaza-bound Global Sumud Flotilla, but first to Yemen, where recent Israeli strikes on two newspaper offices killed 31 Yemeni journalists and media workers, making it the deadliest attack on journalists anywhere in the world in 16 years. Back in 20 seconds.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Bofou Safou” by Amadou & Mariam, performing in our Democracy Now! studio.

Media Options