Topics

Guests

- Malcolm NanceArabic-speaking counterterrorism intelligence officer and combat veteran with over 34 years working clandestine missions in the Middle East, Balkans, South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. He is the author of several books, including The Terrorists of Iraq: Inside the Strategy and Tactics of the Iraq Insurgency 2003-2014.

- Patrick CockburnMiddle East correspondent for The Independent. He’s just back from reporting in Iraq and Syria. His latest book is titled The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution.

The Obama administration is considering a plan to increase the U.S. presence in Iraq by sending 400 to 500 more military personnel as well as establishing a new military base in Anbar province. The United States already has about 3,000 troops, including trainers and advisers, in Iraq. The administration is describing the military personnel as advisers who will help train Iraqi forces in an attempt to retake the city of Ramadi, which fell to the self-described Islamic State last month. Plans to retake Mosul may be pushed off until next year. It was a year ago this week when Islamic State fighters seized Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city. Today the city remains in ISIL’s hands. Advisers close to the White House say it could take decades to defeat ISIL. We discuss the fight against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria with two guests: Malcolm Nance, a retired Arabic-speaking counterterrorism intelligence officer and combat veteran who first worked in Iraq in 1987; and Patrick Cockburn, Middle East correspondent for The Independent, just back from reporting in Iraq and Syria. Cockburn’s latest book is “The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution.”

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The Obama administration is considering a plan to increase the U.S. presence in Iraq by sending 400 to 500 more military personnel as well as establishing a new military base in Anbar province. The United States already has about 3,000 troops, including trainers and advisers, in Iraq. The administration is describing the new military personnel as advisers who will help train Iraqi forces in an attempt to retake the city of Ramadi, which fell to the self-described Islamic State last month. Plans to retake Mosul may be pushed off until next year.

The move comes just days after President Obama acknowledged the U.S. does not yet have a, quote, “complete strategy” to deal with ISIL, which has seized large swaths of Iraq and Syria. It was a year ago this week when Islamic State fighters seized Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city. Today the city remains in ISIL’s hands. Advisers close to the White House say it could take decades to defeat ISIL. At the recent U.S.-Islamic World Forum in Qatar, retired Marine General John Allen said, quote, “This will be a long campaign. Defeating Daesh’s ideology will likely take a generation or more,” he said, using the Arabic name for ISIL.

AMY GOODMAN: Meanwhile, Doctors Without Borders is reporting Iraq is now facing its biggest humanitarian emergency in a generation. Almost three million people have fled war-torn areas of Iraq controlled by the Islamic State. The United Nations estimates 8.2 million Iraqis, nearly 25 percent of the population, will need some kind of humanitarian help this year.

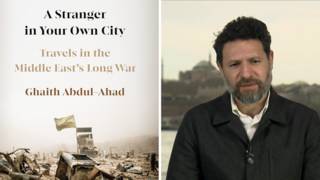

To talk more about the fight against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, we’re joined by two guests. With us here in New York, Malcolm Nance, a retired Arabic-speaking U.S. counterterrorism intelligence officer and combat veteran who first worked in Iraq in 1987. He’s the author of several books, including The Terrorists of Iraq: Inside the Strategy and Tactics of the Iraq Insurgency 2003-2014. His new piece for The Intercept is called ”ISIS Forces That Now Control Ramadi are Ex-Baathist Saddam Loyalists.”

And joining us from London is Patrick Cockburn, Middle East correspondent for The Independent, just back from reporting in Iraq and Syria. His latest book, The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution. His most recent article on Iraq is headlined “War with Isis: As the militant threat grows, so does the West’s self-deception.”

Let’s go first right here to Malcolm Nance. Welcome to Democracy Now! Talk about this latest piece you have written. Talk about the political context for the rise and the power of ISIS today.

MALCOLM NANCE: Well, the biggest misperception now—we’re here on the first anniversary of ISIS taking the city of Mosul, and the biggest misperception that the media has certainly fostered is that ISIS is this new group, which has appeared out of nowhere, they have blitzed across the Middle East, and they have managed to take large swaths of Iraq and Syria—and when, in fact, ISIS is the same group and a conglomeration of groups that we’ve been fighting since the day we invaded Iraq in 2003.

The piece that I wrote in The Intercept, which was extracted from parts of my book, based on my book, The Terrorists of Iraq, is that the former regime loyalists, almost 100,000 of them, who were all taken away from their jobs by Ambassador Bremer’s General Order Number Two, went underground and have been fighting us for the last 13 years, nonstop. However, al-Qaeda in Iraq, which started in 2003, as well, has taken over the upper-level management of these groups. And so, what we have is we have, technically, a mega group of all the former regime loyalist insurgent groups, all of the Iraqi Islamic insurgent groups and the foreign fighters who have used Syria as a base camp. And they now are called ISIS.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But, Malcom Nance, how do you reconcile the fact that the Baathists were largely a secular semi-socialist party when they started, reconciling their ideology and their approach to the world with that of jihadists?

MALCOLM NANCE: Yeah, it’s very interesting, because the jihadists wouldn’t even have been in Iraq until after the U.S. invasion, when the communities that were former Baathists—and you’re right, the Baathists were secularists. The Baath Party was this conglomeration of socialism and secular government that formed into a dictatorship under Saddam Hussein, and also under Hafez al-Assad in Syria. Now—but people who were in Iraq who were Baathists were still Muslims. And as a matter of fact, Saddam Hussein, in the later years, after the U.S. sanctions went into place and after the Iran-Iraq War, started to become more Islamic in name—that is, to co-opt Islam from the people on the street.

The jihadists who came in just after the invasion, the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, came in with their own ideology, which is radical, extremist, almost cultish, Islam. But the Baathists understood that these people had the motivation and the combat capacity to do things that the Baathist forces didn’t have to do, as a matter of fact. You had al-Qaeda in Iraq, who would carry out all the suicide bombings that they wanted. The Baathists would facilitate their entry in from Syria, would build car bombs for them, would gather all of the intelligence against U.S. forces, direct them to it, and they would drive their car bomb into a target—hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of them over the 12 years that Iraq has been in this turmoil.

But it’s a marriage of convenience, to a certain extent. Mosul was a Baathist city. Tikrit was a Baathist city. These are the people who ruled Iraq with an iron fist from 1968 to 2003, and they’re the people who were actually living there. ISIS is just the spearhead of the forces that have now joined them who are Baathists, as well, but ex-Baathist. And they have now taken this patina of the Islamic caliphate on top of that and have sworn their loyalties, but they are the seven-million-person population that owns the place.

AMY GOODMAN: Patrick Cockburn, you’re the Middle East correspondent for The Independent. You’re just back from Iraq and Syria. Do you share this assessment of Malcolm Nance?

PATRICK COCKBURN: No. I think that there’s a big is disconnect between what’s happening now and what happened when Iraq was ruled by the Baath Party. Remember also, the Baath Party and the Iraqi security forces were supremely unsuccessful militarily in 2003, '91 and before, while Islamic State is very successful. Both come out of the Sunni community, et al., but I don't think that the Islamic State is the Baath Party in a new guise.

I mean, one thing that does strike me, though, as very important at the moment, and I’ve just been in northern Iraq and northern Syria talking to people who have come from Islamic State, is that it’s recruiting people all the time. It’s introduced conscription. So, it’s calling up tens of thousands of young men. So it’s an expanding organization. And I don’t think that the outside world, in America or anywhere else, have quite taken on board how tough this organization is and how quickly it’s growing.

And every so often, we hear accounts that, you know, it’s got weaker and so forth, but then it takes another city. It took Mosul. It’s taken Ramadi. It’s taken Palmyra. And now it’s getting close to Aleppo, once the biggest city in Syria. And it’s threatening western Syria. So, this is—people talk about, you know, it’s going to take so many decades to get rid of this organization, but the problem is much more immediate. This is an expanding organization. It’s a military machine that combines religious fanaticism with military expertise. And it’s growing all the time.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Patrick Cockburn, how do you account for this such a fast growth of the organization, especially given the years when there didn’t seem to be any expansion of the jihadists, especially in Iraq?

PATRICK COCKBURN: Well, it looks to the Sunni community in Iraq and Syria, the Sunni Arabs about 20 percent of Iraqis, about 60 percent of Syrians. When the Syrian uprising took place in 2011, there was a whole big new constituency for them. And militarily, they’re much better organized and more effective than the other groups in Syria.

And although they’ve expanded, they still seem to be able to create a real state. I mean, that’s one of the things that struck me talking to people from there. They’ve introduced taxation. They’ve introduced conscription. They’ve introduced horrible laws restricting women from leaving home without a male relative, and you get beaten if you don’t do that. You have to wear the niqab covering the whole face, if you’re a woman. And anybody who opposes them ends up dead very fast. We were talking to the leader of one tribe in Iraq, the Albu Nimr, and 864 of them have been killed since last October. So, this is a savage organization, but it’s a pretty effective one. And it administers everything. It controls education, you know, even fishing rights in the Euphrates River. They have a whole series of instructions, what you can and cannot do. You can’t use explosives. You can’t use poison. So it really does control the area into which it’s expanded, which is greater than the size of Great Britain, and maybe it has at least six million people in it.

AMY GOODMAN: So your main point of disagreement with Malcolm Nance is simply that, while it may have started with different groups, it is far larger than the Baathists of the past?

PATRICK COCKBURN: It’s far larger than al-Qaeda was during the—10 years ago or since. It’s gotten much bigger. You know, the Baathists—if you were a Baathist back then, this is—most of these people are pretty young. You know, if you have to go back to Baathist Iraq, you know, these guys—if all the militants came from there, it would be quite an aging organization. But I don’t think that’s true. I think there’s a connection in the leadership. Some of these people come out of the Iraqi security forces. But I think that it’s developed into a very different type of organization, and, unfortunately, a far more effective one.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s get Malcolm Nance’s response.

MALCOLM NANCE: Well, in some respects, he’s right. It is a very different organization. It has developed in a different way, and it does have a large quantity of young men. But let’s not forget history here. If you were a member of the Saddam Fedayeen at age 20 when the United States invaded, you’d be 35 years old right now, and you would be a mid-level commander with 13 years of extraordinary combat experience under your belt. There were 100,000 Iraqis that we fought when we invaded Iraq. We only killed 6,000 of them in the invasion. That’s a lot, and it’s horrific we even did it, but the very fact is, that left almost 90,000 people who were there to fight us during the eight years that we were in combat with them.

Al-Qaeda in Iraq got all of the news during the time that we were fighting. The United States believed that al-Qaeda in Iraq was everyone that we weren’t fighting. But in fact, we were fighting 30,000 Saddam Fedayeen, 26,000 intelligence agency officers and managers, 6,000 senior Baathist commanders who had Iran-Iraq War experience. These people are the Sunni community of Iraq. They are the men and their children who are the people who own northern and western Iraq. ISIS is just al-Qaeda in Iraq evolved. Once in 2011 Syria fell, that gave them a complete playground, gave them all the lines of communications, weapons, that they could take and use it as a sanctuary to start carving out these areas. But you can’t carve out Anbar province. You can’t carve out Nineveh and Dhi Qar without actually co-opting the communities that are in there who turned against them in 2007 during the Iraq Awakening campaign. It’s just in 2011 they turned back to the people who were going to give them the autonomy they weren’t getting with the al-Maliki government.

So, yes, it’s a young organization. I know this organization. I’ve fought this organization. This organization has tried to kill me. I take it very personally. I see how they operate, and I understand that their tactics, their blitz tactics, are very effective against the Iraqi army, that really doesn’t want to be where they are. But as they take these communities, like Mosul, that community of Mosul, of course—that community in Mosul are the Sunnis who have always been there and who have ruled Iraq, and they are allowing them to come in.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to come back to this conversation after break. Our guests are Malcolm Nance, a retired U.S. counterterrorism intelligence officer and combat veteran. He’s here with us in New York, has a piece in The Intercept. And Patrick Cockburn is with us, just back from Iraq and Syria, Middle East correspondent for The Independent. He’s joining us from London. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Our guests, Patrick Cockburn in London, just back from Iraq and Syria, Middle East correspondent for The Independent, and Malcolm Nance, here with us in New York, retired U.S. counterterrorism intelligence officer and combat veteran, spent many years in Iraq. Juan?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Malcolm Nance, you alluded to your experience in Iraq, and I wanted to go back to some of that experience, because you were in Iraq as far back as 1987, before the Persian Gulf War even. Could you talk about your experiences, your earliest experiences there? And also, your assessment of the Shia community and the Shia militias and their role in the continuing battle with ISIL?

MALCOLM NANCE: The missions that I worked in the 1980s, of course, were in support of the Iran-Iraq War. And as you know, we had a deconfliction problem after Iranian aircraft accidentally struck a U.S. Navy warship. So their were deconfliction missions to Iraq and around Iraq and Kuwait.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Deconfliction? What does that mean?

MALCOLM NANCE: Ah, yeah, that’s—sorry, it’s a technical term which means that we assist them in not mischaracterizing or misidentifying our warships as Iranian navy ships. They were carrying out airstrikes in the Persian Gulf and destroying Iranian tankers. And so, there was a very early mission to deconflict their aircraft attacks away from U.S. warships.

AMY GOODMAN: And the U.S. was supporting both sides.

MALCOLM NANCE: The United States at that time was technically neutral, but it was in the interest of the United States to facilitate the Saudi and Kuwaiti activities in support of Iraq.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And the Shia, and your experience with the Shia militias, as well?

MALCOLM NANCE: Well, I got involved with the Shia very early on. Right after the Operation Desert Storm, I operated in southern Iraq around the areas south of Basra, Umm Qasr, al-Nasiriyah, all these areas down there. And this is where the Shia uprising took place, because the Iraqis, of course, they know their people. And they managed to coordinate and trick General Schwarzkopf into allowing them to use helicopters, and as the Shia of Basra rose up, they used the terms of our peace treaty to carry out attacks on them. And I spent quite a bit of time in Basra, as a matter of fact.

Right now what you’re seeing with the Iraqi Shia militias, the Hashid Shaabi, these popular mobilization units, they call themselves, is very interesting, because, you know, throughout my entire time in Iraq, we fought the Shia. The U.S. Army fought the Shia militias of the Jaish al-Mahdi, which was Muqtada al-Sadr’s organization. And I would have people say to me, “If Sheikh Sistani tells me or Sheikh al-Sadr tells me to attack the Americans, I have to. I’m just obligated to do that.” Well, right now, because of the failure of the Iraqi army, that is how the southern—the Shia of Iraq, who I believe are about 80 percent of the population of Iraq, are mobilizing now in a capacity that they wouldn’t do if they were an Iraqi army unit. They are essentially armed mobs who are going up there and throwing manpower at the ISIS crisis, and with some Iranian support, and just coming in and giving large quantities of manpower to take back cities like Tikrit, Baiji oil refinery. And they believe that they’re going to Ramadi. But when they go there, they’re in it for punishment. They’re not in this in order to maintain the stability of the Shia and Sunni dialogue within Iraq. They are going there to punish the community for bringing ISIS.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go to comments of your former boss—that’s right, former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld—who told The Times of London, quote, “The idea that we could fashion a democracy in Iraq seemed to me unrealistic. I was concerned about it when I first heard those words.” He went on to say, quote, “I’m not one who thinks that our particular template of democracy is appropriate for other countries at every moment of their histories.” Several commentators, including the journalist Bob Woodward, have challenged Rumsfeld’s recent comments. Seven weeks after the U.S. invasion, Rumsfeld said, quote, “If Iraq—with its size, capabilities, resources and its history—is able to move to the path of representative democracy, however bumpy the road, then the impact in the region and the world could be dramatic. Iraq could conceivably become a model.” I wanted to get Patrick Cockburn’s response to this, Rumsfeld basically blaming Bush, saying Bush was wrong.

PATRICK COCKBURN: I think, from the beginning, you have to separate two things: the invasion and the occupation. A lot of Iraqis wanted to get rid of Saddam Hussein, including the Sunni as well as the Shia and the Kurds. But occupation was always—whichever way they tried to play it, was never going to work. The Sunni weren’t going to accept it, because they had been the dominant community. The Shia wanted to be the dominant community. They’re about 60 percent of Iraqis, Shia Arabs. And they didn’t want the U.S. to be the dominant power. And these, of course, were connected, got support from Iran and Syria, because at that time various people in Washington were saying, “Baghdad today, Tehran and Damascus tomorrow.” So the occupation was always going to capsize, whatever way they played it. Since then, there are people saying, “Ah, if we had done something a bit different, it could have worked.” But, you know, all this talk about nation building—one nation doesn’t build another. Occupying powers normally act in their own interests, which is exactly what happened this time around.

AMY GOODMAN: What’s the West’s self-deception here? And what do you think needs to happen, Patrick Cockburn?

PATRICK COCKBURN: Well, talking kind of at the present moment, I think that in Syria and Iraq, the self-deception about the strength of the Islamic State and thinking that it’s somehow going to implode, or if you leave it alone, it’s not going to expand, I think don’t that’s true. And that’s proven by events.

I think also there’s an attempt to rebrand various organizations, like the al-Qaeda affiliate, Jabhat al-Nusra, which has been advancing in northern Syria, and other al-Qaeda-type organizations in the south. And the idea is that somehow this will weaken Assad. What really happens in Syria is that Syrians in Damascus may not much like Assad, but if they’re connected to the government, not just Christians and Alawites and Shia, but ordinary Sunni, they’re terrified of the Islamic State or Jabhat al-Nusra or any of these other extremists taking over. Therefore, they support Assad because they’ve got no alternative. As soon as there—if there was an alternative, then the things might change. But accepting al—now that the whole Syrian opposition is basically dominated by jihadis and al-Qaeda-type organizations, then this means that Assad will continue to get support.

What they ought to do is bomb Islamic State and the others in all circumstances. They should give priority to fighting Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, and they’re not quite doing that. This idea of arming the Sunni tribe has been around for a long time. Maybe you could do that when al-Qaeda in Iraq was powerful in 2006 and '07, but it was never as powerful as the Islamic State was. It was never a state organization. So, I don't—you know, you can meet these tribal leaders in Erbil and in Amman. They’re always promising great things. But what I notice is that there isn’t much resistance locally in Mosul and Ramadi and these other cities. You don’t see assassinations and bombings on a wide scale. So I think that that’s just really a diversionary policy. What I think Washington and its allies should do is give priority, complete priority, to fighting the Islamic State, and they haven’t really done that yet.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Patrick Cockburn, you’ve chronicled the little-noted successes of Kurdish forces in battling against ISIL. Could you talk about that and also whether you think that the map of that region of the world has essentially been redrawn permanently as a result of the continuing conflicts between ethnic, political and religious forces over the last 12 years there?

PATRICK COCKBURN: Yeah, I mean, up in—I was in northern Syria, where there are three big Kurdish enclaves. There are about 2.2 million Syrian Kurds, about 10 percent of the population. They’ve organized themselves pretty well. They are fighting Islamic State. While I was there, they had won a victory at a place called Mount Abdulaziz. They were pretty efficient compared to the Iraqi army or militias, or, indeed, the Syrian army. But so they’re redrawing it for the moment. But they’ve benefited, really, from both the Syrian government and Islamic State fighting each other. Neither of them particularly want the Kurds to have a high degree of autonomy there. So in the long term, if either side in Syria wins, whether Islamic State or the Damascus government, that’s bad news for the Kurds.

But actually, this little state they’ve created there is perhaps the only successful outcome so far of the 2011 uprising in Syria, in that it’s gotten rid of the dictatorial regime of Assad, but it hasn’t been taken over by extreme Islamists. You know, their units of their army are made up of women, that women get 40 percent of the jobs in government, that it’s a holy—it’s a secular society. So, you know, its long-term future is debatable. It’s going to come under a lot of pressure. But the Kurds have a lot of achievements to be proud of there.

AMY GOODMAN: Patrick, last month, The Daily Beast featured an article criticizing your Syria reporting. The author, Muhammad Idrees Ahmad alleges you discount any Syrian nationalist opposition to the Assad regime and that your position is, quote, “Bashar al-Assad is at war with jihadi terrorism; the West has erred in supporting his opponents; and to support the opposition is to support ISIS.” Ahmad goes on to say, quote, “For Cockburn, the situation in Syria is stark: you are with the regime or you are with the terrorists. He is an enthusiast for the war on terror—Bashar al-Assad’s war on terror. He criticizes the U.S. for excluding from its anti-ISIS coalition 'almost all those actually fighting ISIS, including Iran, the Syrian army, the Syrian Kurds and the Shia militias in Iraq.'” Ahmad later accuses you of, quote, “turning a blind eye to the regime’s ongoing slaughter of civilians.” He says, “He is helped in this by the obtrusive barbarism of ISIS, which uses spectacle in the place of scale to force media attention. ISIS has been a godsend for the regime; it has helped divert attention from its crimes—and regime-friendly journalists have obliged in the deflection.” Patrick Cockburn, your response?

PATRICK COCKBURN: Oh, I get a lot of this. You know, anybody who’s going to report the Syrian civil war or the Iraqi civil war is going to be accused by one side or the other of being partisan. And what happens in the Middle East, you know, as always happened, but is happening worse now, is when you analyze something and you say this is the situation, that I don’t think Assad is going to go down, both sides are incredibly brutal in this civil war, then people think you’re justifying it. They mistake analysis for justification. And I’ve had that, really, since 2011.

I remember, you know, a rather nice Syrian I knew in Lebanon. I’d just been in Syria, and I had reported that Assad, for various reasons, was not going to collapse as a lot of media was saying. And as I came back into Syria, I switched on my telephone, and there was the same guy shouting at me, shouting, “Shame on The Independent! Shame on you!” And it was just that I had reported the situation as I saw it—objectively. But he sort of wished that reality was different, and that’s why he was shouting at me. And this is the same sort of stuff.

You know, I can understand the passions involved, that both sides commit appalling atrocities, using maximum violence, whatever they have, against civilians. This is true of the Assad government dropping barrel bombs on civilians. It’s true on the Islamic State. Five, six hundred members of another tribe in Syria were massacred. So I can understand how people feel like that. And it’s part of the war, so, yeah, I get attacked like that. I’m sure I’ll be attacked again. And there’s nothing much I can really do about that.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Malcolm Nance, in closing, I’d like to ask you, here we are, 12 years after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, and you’ve been—you participated in, were involved in much of the regime change that occurred there. What’s your assessment of the failures of the United States in Iraq and its responsibility for the current situation?

MALCOLM NANCE: To take nothing away from the people who fought that war, that war should never have been fought. I’m saying this not as someone who writes books; I’m saying this as an intelligence professional. Invading Iraq after 2003 would have been akin to invading Mexico after Pearl Harbor. It had nothing to do with 9/11. The intelligence did not support it.

I had an incident—not an incident, but an event, which occurred about six months before the invasion, and I met a very high-level intelligence person who was a personal friend of Colin Powell, and he said, “Malcolm, what’s your assessment of this? They’re talking about the communications intercept that we got from the Iraqis, that the president had put out to justify part of the war.” And I said, “I’ve been doing this for decades. I just don’t see it. The intelligence is not there. We don’t have direct links to 9/11.” Afghanistan, where I had just come back from, is full of al-Qaeda. They had gone over the mountain to Pakistan. This is a strategic mistake. It’s done.

And what we need to do now is we have fostered the Iraqi government, we have tried to help them facilitate their growth, we have tried to help democracy, despite what Donald Rumsfeld says. However, we’re at the point now where the Pandora’s box is open and we have unleashed a group, which has taken al-Qaeda ideology to its exact extreme. They have carved out exactly what Osama bin Laden had been saying for almost three decades, that he wanted. He wanted an Islamic caliphate in the heart of the Middle East. They have achieved that nominally. They control the roads. They control a few cities. But right now we’re doing a linear battle using forces we know that can’t fight, or won’t fight. Some Iraqi units are brilliant, like the Golden Division, the Iraqi Special Operations Forces. But what we have is we have a situation where we are going to have to take them on.

Now, does it require U.S. troops? I don’t believe it does. Will it require additional training? Yes. We’re going to have to create forces which are going to have to go after ISIS where ISIS lives. Right now we’re trying to take back Ramadi and Mosul, but ISIS doesn’t live on every road in between there. You have to cut them off, you have to isolate them. The strategic policy of the Pentagon right now is do it from the air. It can’t be done from the air. We’re going to have to get a lot more air power and people who are going to go in there and confront them and cut them off.

AMY GOODMAN: So why are you talking about anything different than happened 12 years ago, if you’re talking about re-engage? Already thousands of troops are there. Now President Obama, probably today, is announcing another 500 troops.

MALCOLM NANCE: The president is in damage-control mode. What we have is flooding here, the uncontrollable flooding in a situation that didn’t need to be underwater. And so, what he’s trying to do is incrementally do this so that he doesn’t have to introduce large forces that will get attacked. If we had stayed in Iraq after 2011, we would be well past the 4,693 dead that we had in that war. We’d be pushing 6,000 dead troops at this point. ISIS and all these other groups would be attacking us on a minute-to-minute basis, and that’s all you would be hearing about, is the failure of us not to get out of Iraq.

Now we have to facilitate the Iraqis, and where we can in Syria, and work with our Arab partners to try to degrade this organization to the point where they will lose their mobility. And it’s interesting, Patrick Cockburn had just mentioned about supporting—you know, everyone in Syria now is rallying around the Assad government, and that’s very true, a government we wanted to see gone two years ago. But the alternative, other than the Free Syrian Army groups and al-Qaeda’s Jabhat al-Nusra, is ISIS. And they are absolutists. They are going to eliminate anyone in their path. So now we have a completely different dynamic than we had 12 years ago.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, this is a discussion we will certainly continue on Democracy Now! I want to thank Patrick Cockburn in London, Middle East correspondent for The Independent, just back from Syria and Iraq, and Malcolm Nance, here with us in New York, retired U.S. counterterrorism intelligence officer and U.S. combat veteran.

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, we go to Louisiana. What will happen with Albert Woodfox, the man, the prisoner, who has been held longer than any prisoner in solitary confinement in this country, for 42 years? Stay with us.

Media Options