Topics

Guests

- Conor FoleyJournalist and veteran aid relief worker who has worked for several humanitarian groups. His new book is The Thin Blue Line: How Humanitarianism Went to War.

Conor Foley has been a humanitarian aid worker in over a dozen conflict zones, including Kosovo, Afghanistan and northern Uganda. His latest book traces the development of the doctrine of humanitarian intervention and how it’s been used to justify the use of force by powerful states. It’s called The Thin Blue Line: How Humanitarianism Went to War. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

JUAN GONZALEZ: The impulse to act, to do something immediate and effective to alleviate suffering and stop conflict, drives many who are concerned about human rights and injustice. But this impulse can easily be turned into a call for military intervention.

Before 2003, American and British political figures repeatedly spoke about “responsibility to act” to stop the abuses in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Legal scholars and advocates of external military intervention during humanitarian crises now speak of the “responsibility to protect” as an emerging norm within international law. But humanitarian interventions, from Somalia to Kosovo to Iraq, have gone disastrously wrong with dire consequences for the populations who were meant to be protected.

AMY GOODMAN: Our next guest has been a humanitarian aid worker in over a dozen conflict zones, including Kosovo, Afghanistan, northern Uganda. His latest book traces the development of the doctrine of humanitarian intervention and how it’s been used to justify the use of force by powerful states. It’s called The Thin Blue Line: How Humanitarianism Went to War. Conor Foley joins us here in the firehouse studio.

Welcome to Democracy Now! How is it used? How is humanitarianism and humanitarian intervention used?

CONOR FOLEY: Well, I think over the last ten years there has been a move towards, as you say, a militarization of humanitarian interventions in two quite different ways. Firstly, I think there will be cases where the only way in which you can stop suffering, in which you can save people’s lives, is through military intervention. And we see UN-authorized peacekeeping missions in about twenty countries at the moment. The biggest one is in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

But at the same time, particularly, as you said, in the run-up to Iraq, they, George Bush and Tony Blair, have been using humanitarian arguments to justify regime change on human rights grounds. About ten years ago, Tony Blair came to the United States and made a speech where he outlined this new doctrine and where he said it was no longer necessary to have UN authorization to invade another country. This was the time of the Kosovo conflict. And since then, there has been a huge crisis for us as humanitarian aid workers, because we work often in conflict zones alongside troops, but we’re also increasingly being identified as part of occupation forces. And certainly in Afghanistan, where I’ve spent much of a couple of years working, we’ve become increasingly seen as part of that occupation force.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk more about Afghanistan.

CONOR FOLEY: I went to Afghanistan after 9/11 and set up a legal aid program there for returning refugees. When we first arrived, we were seen as neutral. We operated quite easily and openly. I mean, I used to walk to work every day.

But then, over 2003, 2004, the impact of Iraq, the impact of the torture in Abu Ghraib, we became increasingly targeted by the Taliban. Several of my friends and colleagues were murdered. And as the war has escalated, the attempts, particularly by the Bush administration to integrate aid into counterinsurgency operations, has, I think, meant that we have sacrificed our neutrality. And just as happened in Iraq, we’ve been seen to be part of an occupation force.

And that’s been a terrible tragedy in human terms — obviously, several friends and colleagues are now dead — but also for the people of Afghanistan, when we can no longer get access to the areas where we’re needed. And because we don’t want to object to being seen as a militarized force, we’ve had to restrict our movements, restrict our work. And it means we’re not doing our jobs properly anymore.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, this urge to occupy countries for humanitarian reasons obviously is not new. I mean, I can think back to the Spanish-American War, when the American public was whipped up into a frenzy over the supposed atrocities of the Spanish government against the people of Cuba to justify the US occupation, a war with Spain. But could you talk about the impact, especially in the last forty or fifty years, of the mass media, especially television, the idea that these pictures now of what is occurring in these various countries now come to England, to the United States, to Australia, and the public therefore feels a much closer sort of relationship to what’s going on there?

CONOR FOLEY: Yeah, the CNN factor. I think you’re right. There is a long history to governments using the doctrine of humanitarianism in order to invade other countries. I mean, Hitler said it when he dismembered Czechoslovakia. He went into the Sudetenland, was part of a — to stop the persecution of people there.

I think modern-day humanitarianism really dates back to the end of the first Gulf War. If you remember, after Saddam Hussein’s forces were defeated and expelled from Kuwait, the Kurds in the north rose up, and the Republican Guard were turned on them. And the UN Security Council passed a resolution demanding humanitarian access, and because of the CNN factor, I mean, people could see that the Iraqi armed forces are being easily beaten, and they could also see that they were turning on the Kurds. They could tell that Saddam Hussein had used chemical weapons against the Kurds only three years before, so there was the real prospect of another genocide. There was two million Kurds fled to the border with Turkey. The Turkish forces closed the border, and there was about a thousand people dying every day. And so, there was a demand for intervention, and the UN Security Council authorized an intervention force. So, really, I think that was the first time that there had been humanitarian intervention of that sort authorized by the United Nations. And as I said, there are now maybe twenty UN-authorized peacekeeping forces around the world.

I think the problem really has been the manipulation of that doctrine, particularly over Iraq, and the decision by some Western powers, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom, to say, “We will be the judge, jury and executioner, when it comes to humanitarian interventions. We’ll decide. We have a responsibility to act. And we’ll exercise that, even if the UN doesn’t act itself.” And at the same time, we’ve seen that the governments of both Britain and United States acted illegally over Iraq, and the government of the United States clearly acted illegally in its conduct of the war on terror. So there’s an element of double standards there. They’re saying we’re going to intervene to uphold democracy and protect human rights, yet at the same time, in our national interests, we’ll disregard human rights, we’ll disregard international law, and we’ll disregard the laws of our own country.

JUAN GONZALEZ: What about a place like Darfur? Obviously there’s a huge movement here in this country and others calling for the Western powers to act to prevent the killings there.

CONOR FOLEY: I was talking last night to some people who have just come from Darfur. And I think most people on the ground, most aid workers on the ground, have been very uneasy about what’s happened in Darfur over the last four or five years. Clearly, there’s a humanitarian crisis. Clearly, tens of thousands of people have lost their lives. And clearly, there is a case that the Sudanese government has implemented the policy of genocide. The Sudanese president is now indicted for it, for genocide, by the International Criminal Court.

Yet there’s also clearly part of the neoconservative agenda to at least threaten military force against Darfur, which isn’t supported by the aid workers. I mean, aid workers have released statements saying, “If you were to start unilateral military action without UN authorization, we would have to leave. We could no longer take care of the people in the camps, if the Western forces intervened.” Currently, there are millions of people who are completely dependent on humanitarian aid to stay alive. If you used — if you introduced force at this point, firstly, there’s a question of whether or not it’s credible with the US and the UK bogged down in Afghanistan and Iraq, but secondly, even the threats of armed force are making it very difficult for humanitarian organizations to do their job. And I think there’s been problems.

I mean, this happened in Kosovo where I was working. Clearly, there was a humanitarian crisis simmering in Kosovo, but the decision by NATO to start bombing turned what was a fairly low-level crisis, where hundreds of people are being killed, into a massive crisis, where thousands of people were killed, and hundreds of thousands of people were driven from their homes.

So I think there’s a dilemma in Darfur, and the aid workers are concerned about that dilemma. Yes, we want international attention in the Darfur region, but most people think that Western military intervention would be counterproductive.

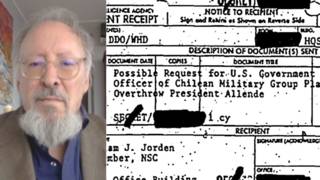

AMY GOODMAN: Conor Foley, I wanted to ask you about the ICC, the International Criminal Court. You mentioned Sudan and its head. You were in Britain with Amnesty, involved with the campaign to hold Pinochet accountable, to get him arrested. What about that? Who gets indicted? Who doesn’t? And what do you think of the latest headlines, just reading today about people in the United States, two-thirds of Americans wanting an investigation, 40 percent wanting prosecution of Bush officials?

CONOR FOLEY: Yes. In fact, I went into the field first in Kosovo, because I’d been working at Amnesty and was involved in the Pinochet case. The principle is fairly straightforward. There are certain crimes defined under international law — torture, genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity — where people can be prosecuted throughout the world, irrespective of their nationality or where the crime was committed or the nationality of the victims.

So, the Pinochet case happened, because he committed torture in Chile during the coup, and then he stepped down and gave himself an amnesty and said, “As the former head of state, I can’t be prosecuted.” He went to Britain, and the Spanish said, well, under universal jurisdiction, Spain, Chile and the United Kingdom have all ratified the UN Convention Against Torture, and therefore you can be prosecuted. And the House of Lords issued a judgment saying that would be the case. I think that was a very significant judgment. And it was around the time that the International Criminal Court was being created, and it was around the time that human rights arguments were being used to justify armed intervention in Kosovo.

And I think it’s got some relevance for the situation for you here in America today, because the United States is a signatory of the UN Convention Against Torture. There’s a clear prima facie case that torture has been committed and was authorized at the highest levels by the previous administration, in breach not just of US obligations under international law, but US obligations under domestic law. So I think there’s a clear case that you, the people of the United States, need to hold your previous leaders to account. I think there should be a commission of inquiry. It’s very, very good that there’s 75 percent support for a commission of inquiry. I saw there was 40 percent support for prosecutions. Clearly, first you have to have an inquiry. First you have to find out if the law was broken. I think there’s a whole number of documents that possibly need to be declassified. There needs to be a thorough debate about this.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And in the thirty seconds or so that we have left, any sense from you in terms of what’s the humanitarian crisis that most poses the threat of escalating now into military intervention?

CONOR FOLEY: Well, the big crisis you have is Afghanistan, where you already — the US has already intervened. There are looming crises. Rather, the Democratic Republic of Congo is the big one, and there is already a big peacekeeping force there.

I think the point I’d like to end, though, is just on the need to have — not to have double standards. The United States has a proud tradition of upholding democracy and human rights throughout the world. That reputation has been tarnished. And I think you owe it to the rest of the world to redeem that reputation by finding out exactly what happened under the previous administration and holding people to account for it.

AMY GOODMAN: Conor Foley, we want to thank you for being with us. Have a safe trip back to Brazil. His new book is called The Thin Blue Line: How Humanitarianism Went to War.

Media Options