Guests

- Eric Schlosserauthor of numerous books, including the best-selling Fast Food Nation. His new book is Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety.

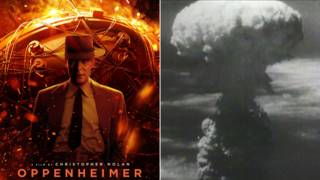

Thirty-three years ago to the day, the United States narrowly missed a nuclear holocaust on its soil. The so-called “Damascus Accident” involved a Titan II intercontinental ballistic missile mishap at a launch complex outside Damascus, Arkansas. During a routine maintenance procedure, a young worker accidentally dropped a nine-pound tool in the silo, piercing the missile’s skin and causing a major leak of flammable rocket fuel. Sitting on top of that Titan II was the most powerful thermonuclear warhead ever deployed on an American missile. The weapon was about 600 times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. For the next nine hours, a group of airmen put themselves at grave risk to save the missile and prevent a massive explosion that would have caused incalculable damage. The story is detailed in Eric Schlosser’s new book, “Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety,” which explores how often the United States has come within a hair’s breadth of a domestic nuclear detonation or an accidental war. Drawing on thousands of pages of recently declassified government documents and interviews with scores of military personnel and nuclear scientists, Schlosser shows that America’s nuclear weapons pose a grave risk to humankind.

Transcript

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Thirty-three years ago today, the United States narrowly missed a nuclear holocaust on its soil that would have dwarfed the horrors of the Hiroshima bomb blast that killed approximately 140,000 people. The so-called “Damascus Accident” involved a Titan II intercontinental ballistic missile mishap at a launch complex outside Damascus, Arkansas. During a routine maintenance procedure, a young worker accidentally dropped a nine-pound tool in the silo, piercing the missile’s skin and causing a major leak of flammable rocket fuel. Sitting on top of that Titan II was the most powerful thermonuclear warhead ever deployed on an American missile. The weapon was about 600 times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. For the next nine hours, a group of airmen put themselves at grave risk to save the missile and prevent a massive explosion that would have caused incalculable damage.

AMY GOODMAN: To find out what happened next, we turn to a shocking new book called Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety. In it, author Eric Schlosser reveals how often the United States has come within a hair’s breadth of a domestic nuclear detonation or an accidental war. Drawing on thousands of pages of recently declassified government documents and interviews with scores of military personnel and nuclear scientists, Schlosser shows that America’s nuclear weapons pose a grave risk to humankind. We’re joined right now by Eric Schlosser, author of a number of books, including the best-selling Fast Food Nation.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

ERIC SCHLOSSER: Thanks for having me.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about that story 33 years ago today.

ERIC SCHLOSSER: Yeah, 33 years ago, during a routine maintenance procedure, a tool was dropped, and it set in motion events that could have led to the destruction of the state of Arkansas. And it just so happened that Bill Clinton was the governor at the time. Vice President Mondale was in the state at the time. And it’s one of those events that literally could have changed the course of history.

So the book is a minute-by-minute account of this nuclear weapons accident and its unfolding, but I use that narrative as a way to look at the management of our nuclear weapons, really from the dawn of the nuclear era to this day. A great deal has been in the media lately about Pakistani nuclear program, Indian nuclear program, Iran’s, but not enough attention has been paid to our own and the problems that we’ve had in the management of our nuclear weapons. And it’s a subject that I think is really, really urgent.

It’s interesting, as I was watching Bill McKibben, who I consider a true American hero, and I was just seeing the title of this show, Democracy Now!, the whole system of managing nuclear weapons is inherently authoritarian. And if you look at the kind of secrecy that we have now in this country and the national security state, it all stems from the development of the atomic bomb, the secrecy around it. And the real point of this book is to provide information to Americans that the government has worked very hard to suppress, to deny, an enormous amount of disinformation and misinformation about our weapons program.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: You also point out, Eric Schlosser, that there is a link between the amount of secrecy around nuclear weapons and the level of their unsafety.

ERIC SCHLOSSER: Yeah.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Could you elaborate? Could you explain why that’s the case?

ERIC SCHLOSSER: Well, during the Cold War, and to a certain extent today, there was such intense, compartmentalized secrecy within the government, that, for example, the engineers and physicists who were designing the weapons weren’t allowed to know how the weapons were being used in the field. And the Air Force and Navy and Army personnel who were handling nuclear weapons didn’t know about the safety problems or safety issues that the designers knew.

So, one of the people I write about in the book is an engineer named Robert Peurifoy, who rose to be a vice president at the Sandia National Laboratories and is a remarkable man who realized that our nuclear weapons might be unsafe and pose a threat of accidental detonation. Again, in the book, I go through a number of instances that we almost had American weapons detonate on American soil. And so, I write about his effort to bring modern safety devices to our nuclear weapons.

Through the Freedom of Information Act, I was able to get about a 250-page document that listed all these different accidents, mistakes, short circuits, fires involving nuclear weapons. And I showed it to him, and he had never seen it. And this is somebody who for decades was at the heart of our nuclear weapons establishment. So the secrecy was so intense that the Air Force wasn’t telling the weapons designers problems that they were having in the field.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us some of those accidents, some of those near misses, and then how things are being handled today.

ERIC SCHLOSSER: Yeah, I mean, one of the most significant near misses occurred just three days after John F. Kennedy was inaugurated. A B-52 bomber broke apart in the sky over North Carolina, and as it was breaking apart, the centrifugal forces affecting the plane pulled a lanyard in the cockpit, which released one of the hydrogen bombs that it was carrying. And the weapon behaved as though it had been released over the Soviet Union, over an enemy target deliberately. And it went through all of its arming stages, except one. And there was one switch that prevented it from detonating in North Carolina. And that switch later was found to be defective and would never be put into a plane today. Stray electricity in the bomber as it was disintegrating could have detonated the bomb.

The government denied at the time there was ever any possibility that that weapon could have detonated. Again and again, there have been those sort of denials. But I obtained documents through the Freedom of Information Act that said conclusively that that weapon could have detonated. I interviewed former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who had just literally entered the administration and was terrified when he was told the news of this accident when it occurred. The official list of nuclear weapons accidents that the Pentagon puts out lists 32, but the real number is many, many higher than that. And again—

AMY GOODMAN: What are some of the more recent ones?

ERIC SCHLOSSER: Well, just this summer, two of our three Minuteman missile wings were cited for safety violations. A few years ago, the Air Force’s largest storage facility for nuclear weapons, the group that ran it was decertified for safety violations. And one of the more concerning things right now—this sounds like, you know, a Hollywood movie—is the potential vulnerability of our nuclear command and control system being hacked to cyber-attack.

The Defense Science Board put out a report this year that the vulnerability of our command and control system to hacking has never been fully assessed. There were Senate hearings on it this spring that didn’t get very much attention. But in 2010, 50 of our missiles suddenly went offline, and the launch control centers were unable to communicate with them for an hour. And it later turned out to be one computer chip was improperly installed in a processor. But what we’ve seen with Snowden and a relatively low-level private contractor able to obtain the top secrets of the most secret intelligence agency, the cryptography and some of the code management of our nuclear weapons is being done by private contractors. And—

AMY GOODMAN: Who’s doing it?

ERIC SCHLOSSER: I think Boeing is doing some of it. And again, they may be doing a wonderful job, but when you’re talking about nuclear weapons, there is no margin for error. And if you managed nuclear weapons successfully for 40 years, that’s terrific, but if you make one severe error and one of these things detonate, the consequences are going to be unimaginable.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: You’ve also said that the command and control structure—system in place for nuclear weapons has actually weakened since the end of the Cold War. Is that right?

ERIC SCHLOSSER: One of the things that’s happened and one of the problems the Air Force is having is, once the Cold War ended—and during the Cold War, having control of nuclear weapons was a high-prestige occupation in the Air Force and the Navy, but since the Cold War, it’s been seen as a career dead end. And so, there have been all kinds of management issues, underinvestment—and I’m not saying we should be building, you know, hundreds and hundreds of new bombers or—but if you’re going to have nuclear weapons, no expense should be spared in their proper management.

AMY GOODMAN: How many do we have?

ERIC SCHLOSSER: And what I was going to say is, some of the systems that we have right now are 30, 40 years old. We’re still relying on B-52 bombers as our main nuclear bomber. Those are 60 years old. They haven’t built one since the Kennedy administration. And the Titan II missile that I write about at some length in my book, one of the problems and one of the causes of the accident was that it was an obsolete weapon system. Secretary of Defense McNamara had wanted to retire it in the mid-1960s, and it was still on alert in the 1980s. And again, with nuclear weapons, the margin of error is very, very small.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to President Obama in June. He was speaking in Berlin, in Germany, and called for nuclear reductions.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA: Peace with justice means pursuing the security of a world without nuclear weapons, no matter how distant that dream may be. And so, as president, I’ve strengthened our efforts to stop the spread of nuclear weapons and reduce the number and role of America’s nuclear weapons. Because of the New START Treaty, we’re on track to cut American- and Russian-deployed nuclear warheads to their lowest levels since the 1950s.

AMY GOODMAN: That was President Obama speaking in Berlin in June. Shortly afterwards, Fox News contributor Charles Krauthammer criticized Obama for discussing nuclear arms reduction.

CHARLES KRAUTHAMMER: The idea that we’re going to be any safer if we have a thousand rather than 1,500 warheads is absurd. So why is he doing this? Number one, he’s been obsessed with nuclear weapons and reducing them ever since he was a student at Columbia and thought that the freeze, which was the stupidest strategic idea of the '80s, wasn't enough of a reduction, and second, because I think that’s all he’s got.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Charles Krauthammer on Fox. Eric Schlosser?

ERIC SCHLOSSER: Right. As an analyst, I think that given his record on the Iraq War, nothing he says should be taken seriously. The fact of the matter is, every nuclear weapon is an accident waiting to happen or a potential act of mass murder. And the fewer nuclear weapons there are, the less likely there is to be a disaster. And I think that President Obama, on this issue, has been quite courageous in calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons. It’s something that presidents have sought in one way or another since the end of the Second World War. And I think it’s urgent that there be a real arms control and reduction, not just of our arsenal, but of worldwide arsenals of nuclear weapons.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, I want to turn to a video released by the anti-nuclear weapons group Global Zero that shows many members of Congress don’t even know how many nuclear weapons the United States has. Here, members of Global Zero approach Republican Representative Morgan Griffith of Virginia, Republican Representative Blaine Luetkemeyer of Missouri, Republican Representative Rob Wittman of Virginia, and Democratic Representative Pedro Pierluisi of Puerto Rico, Republican Representative Duncan Hunter of California, Republican Representative Mark Amodei of Nevada and Republican Representative Bill Flores of Texas.

GLOBAL ZERO INTERVIEWER: Do you happen to know roughly know how many nuclear weapons we do have?

REP. MORGAN GRIFFITH: Uh…

REP. BLAINE LEUTKEMEYER: Well…

REP. ROB WITTMAN: The current arsenal, I don’t have an exact number.

REP. TOM McCLINTOCK: My understanding is about 300.

REP. PEDRO PIERLUISI: No, no, it’s much more than that.

GLOBAL ZERO INTERVIEWER: It’s more than 15,000?

REP. PEDRO PIERLUISI: In terms of nuclear heads? Of course.

GLOBAL ZERO INTERVIEWER: More than 15,000? Really?

REP. PEDRO PIERLUISI: Well, I don’t know.

GLOBAL ZERO INTERVIEWER: Do you have any idea about how many nuclear weapons we have?

REP. DUNCAN HUNTER: Uh, no.

REP. MARK AMODEI: Nope, not the exact number.

REP. BILL FLORES: It changes every day.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: According to the group Global Zero, more than 70 members of Congress were polled, and 99 percent of them did not know, even roughly speaking, how many nuclear weapons the United States has. Eric Schlosser, your remarks on that?

ERIC SCHLOSSER: It’s not an entirely fair question, because the numbers are very different whether they’re being counted for the SALT Treaty, how many are in reserve, etc. And so, it’s a difficult thing to say specifically. We have about 1,500 under the SALT Treaty deployed. We have a few thousand other—

AMY GOODMAN: And where are they?

ERIC SCHLOSSER: —in reserve. They’re mainly on our nuclear submarines that are at sea. We have 450 strategic land-based missiles that are in the northern Midwest. But it’s important to keep in mind that there is grounds for optimism. At the height of the Cold War, the United States had 32,000 nuclear weapons, and the Soviet Union had 35,000. So, right now, the number of weapons that both the Soviet Union and the United States have on alert, ready to be launched, combined, is maybe 2,000, 2,500. So, to go from 60,000 to 2,500, you know, 8,000 to 10,000, is a huge achievement. But there needs to be much greater reductions.

AMY GOODMAN: Is there a possibility of a domestic Stuxnet, you know, like the U.S. released against Iran, a virus in the—that would affect command and control?

ERIC SCHLOSSER: It’s a great concern. You know, these weapons are not connected to the Internet, but there are command information systems that run software. During the Cold War, Zbigniew Brzezinski was woken up in the middle of the night. He was national security adviser. He was told the United States was under attack. He got another call and was basically preparing to call President Carter and advise a retaliation. And it turned out that there was a faulty computer chip in the NORAD computers that was saying that Soviet missiles were coming towards the United States, and they weren’t. So, as long as you have a weapons stance in which we need to be able to retaliate immediately, it puts enormous pressure on acting quickly, and there’s are all kinds of possibility for error.

AMY GOODMAN: So, what has to be done?

ERIC SCHLOSSER: I think, firstly, the reason that I wrote the book is, in a democracy, these sort of decisions need to be debated by the American people. And really, since 1944 or 1945, fundamental decisions about nuclear weapons have been made—

AMY GOODMAN: We have 20 seconds.

ERIC SCHLOSSER: —by a small group of policymakers acting in secret. So, firstly, we need openness. Secondly, we need a debate. And thirdly, we need fewer nuclear weapons, much more carefully managed, not only in this country, but in every country.

AMY GOODMAN: Eric Schlosser, we want to thank you for being with us. Command and Control is the book. It has just come out. Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety.

Media Options