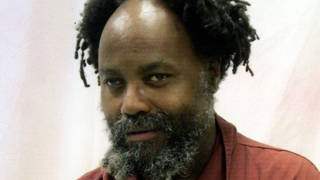

Index on Censorship. Noelle Hanrahan discusses the process of recording the voices of inmates and the banning of Mumia Abu-Jamal’s radio essays on public radio All Things Considered. Abu-Jamal is incarcerated in Huntington on death row, convicted of killing Daniel Faulkner, a police officer. Hanrahan was banned for a year after crediting a photo she took of the prison facility. To continue the recordings, she asked the UK magazine, Index on Censorship, to assign the story to her, because the prison facility allowed foreign requests for access to prisoners. Hanrahan hired Janice Leber, an engineer from KPFA, and Nolen Edmonston, a photographer, who were sent in to continue the recordings. After the trauma of strip searches, they were finally allowed to continue recording Abu-Jamal on condition that a prison administrator was present. Abu-Jamal was a broadcast journalist and recorded over 400 commentaries, mentioning his case only twice. One of the reasons NPR rejected his commentaries was because he may mention his case.

Segment Subject: Mumia Abu-Jamal, All Things Censored, Prison Radio Project

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN:

Today on Democracy Now!, we air the latest commentaries of Mumia Abu-Jamal, an inmate on Pennsylvania’s death row. Mumia Abu-Jamal is a former radio reporter and Black Panther, who was tried and convicted for the 1981 murder of Philadelphia police officer Daniel Faulkner. His supporters say that Mumia was wrongfully convicted and have cited two dozen examples of serious trial errors, including the use of Mumia’s political beliefs against him. As a result, a national and international movement has emerged calling for a new trial. In fact, the movement has been so powerful that Mumia’s execution, slated for August of 1995, was ultimately blocked. At the same time, Pennsylvania state officials, including police and prosecutors, are equally adamant that Mumia is guilty of murdering Officer Faulkner and are defending his trial and conviction as legitimate.

Throughout the debate over whether Mumia had a fair trial, however, prison officials and leading politicians have repeatedly sought to prevent him from publishing, broadcasting and having access to the media while on death row. In May 1994, after an outcry from the Fraternal Order of Police in Pennsylvania, National Public Radio announced that they would not broadcast the commentaries that they had recorded and promoted. In February of 1995, after publishing his book Live from Death Row, prison officials barred Mumia from giving press interviews, a ban that was later lifted after a federal lawsuit. And just this past few months, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections ruled that all prisoners in the state could no longer be recorded or videotaped. And so we begin with the first of the commentaries that we will be airing over the next two weeks.

MUMIA ABU-JAMAL: My name is Mumia Abu-Jamal. I’m a journalist, a husband, a father, a grandfather and an African American. I live in the fastest-growing public housing tract in America. I’ve been a resident on Pennsylvania’s death row for more than fifteen years. That’s what capital punishment really means. “Those that ain’t got the capital gets the punishment” is the old saying. Once again we see the inherent truths that lie in the proverbs of the poor.

That old saying echoed when it was announced that the district attorney of Delaware Country, Patrick Meehan, would not seek the death penalty in the case of John E. du Pont, the wealthy corporate heir charged with the shooting death of Olympic champion David Schultz. The Delaware County DA’s Office said no aggravated circumstances justifying the death sentence existed. Could it be that du Pont’s personal wealth, estimated at over $400 million, was a factor? In one fell swoop, the state ensured that while millionaires may be murderers, they are not eligible for that preserve of the poor — America’s death row.

As the case of O.J. Simpson showed us, the state is very selective in who it chooses to include in its macabre club of death. O.J., a bona fide celebrity, corporate pitchman, sports legend and millionaire, was deemed, even though a suspect in a double-murder, not fit for a death sentence. So, whether or not one is of the opinion that Mr. Simpson was either innocent or guilty, a point remains that before the trial actually began, the DA of Los Angeles decided no death penalty for O.J. Millionaires need not apply. As it was for Mr. Simpson, so it was for Mr. du Pont. Simpson’s wealth, compared to du Pont’s, makes him look like a pauper.

As for du Pont, consider, if you will, the incredible spectacle of the DA, with all the identical facts, announcing he or she would not be seeking the death penalty if du Pont was the victim. I’m sure we can all agree that would be impossible. Any poor man who slays a wealthy man will have the weight of the system fall on him like a ton of bricks. For a wealthy man, however, who finds himself charged with killing a poor man, the system becomes user-friendly. Why should this be so? It’s because the system serves the interest of the wealthy. It is their system. In essence, when a poor person comes before the court, he or she faces two things: the offense and being poor. I am not suggesting that Mr. du Pont, or anyone else for that matter, should be sentenced to death. I’m just noting how and why the death sentence is reserved for some and off-limits to others. The death sentence remains a prerogative of the poor.

From death row, this is Mumia Abu-Jamal.

AMY GOODMAN:

Mumia Abu-Jamal, recorded last October at SCI-Greene, the prison where he is on death row in Pennsylvania. And right now we’re joined in the studio by Noelle Hanrahan, and Noelle is the head of the Prison Radio Project based in San Francisco, California. And she is the person responsible for that recording, although she didn’t go in herself on that day.

Noelle, welcome to Democracy Now! And I want to say thank you very much for making this all possible for us on Democracy Now! to air the commentaries of Mumia Abu-Jamal. Tell us how this all happened.

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

Well, originally, in 1992, I was producing Pacifica’s national coverage of the Robert Alton Harris execution, and we produced twelve hours of coverage with a hundred different interviews, but we were unable to get the voice of an inmate on the air. And I thought real radio, radio that would be important for people to listen to, needed to have a voice of an inmate. When California started executing after twenty-five years again, we needed to actually have that voice, and we couldn’t find one, for a number of reasons. One, all of the different lawyers were very worried that if their inmate or their prisoner was interviewed, that it would bump him up the list, that there were 300 people on death row at that time, and if their guy went on the radio, that he’d be executed faster. Another reason is that sometimes inmates have mental or psychological problems. Often, if they’re on death row for ten years, that can be really psychologically debilitating. So it was very difficult to find someone. I read Mumia’s writings and went out to Huntington, where he was incarcerated at the time in July of ’92, and got those recordings. After a couple more trips — and we aired them extensively on Pacifica stations — after a couple more trips, we got it to the point where his recordings were good enough to be on National Public Radio and All Things Considered.

AMY GOODMAN:

And what happened?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

In 1994 we pitched All Things Considered to make him a regular commentator, and they accepted. They made him a new regular commentator. He would have reached seven to ten million people. We went out, recorded another set of commentaries, brought them back. They promoed them for a month, big New York Times story, and the day before they were going to air, twelve hours before they were going to air, they were pulled, at the behest, we think, of the Fraternal Order of Police and Bob Dole.

AMY GOODMAN:

And the Fraternal Order of Police is the police union in Pennsylvania.

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

Yes, and actually it was connected up with the national Fraternal Order of Police organization that mobilized their membership nationwide to put pressure on National Public Radio to yank his commentaries.

AMY GOODMAN:

And of course they’re saying you shouldn’t be glorifying a cop killer. Mumia Abu-Jamal was convicted of killing officer Daniel Faulkner in 1981. What’s your response to that?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

My response is that we are conducting the death penalty in the United States, and it’s going to be escalating, and we need to really reach beyond the prison walls and hear about it. If we’re paying for it, if we’re conducting executions at the pace that they’re going to happen, then we really need to explore the question fully. And I think, as a journalist, those voices need to be heard in the debate and that this country must debate a question of this moral extreme, that we really need to have a full debate. And the other side, I think, is actually wanting to silence the question and to limit debate. So many Americans are affected by criminal justice issues that they need to hear those issues talked about and explained from a variety of different sources. And because we have over five million people under correctional control, these are issues that are daily in the lives of people in this country that we need a fuller discussion on.

AMY GOODMAN:

So how were these latest recordings made, made just this past October, the first recordings made of Mumia Abu-Jamal’s commentaries since NPR pulled them from the air?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

We went out to SCI-Greene with a tape machine, digital audio tape recorder, and we went to Mumia’s cell block, and we recorded him using a wireless mic. He’s actually in a non-contact visiting room, which means he’s beyond Plexiglas and mesh —- he’s behind Plexiglas and mesh. So we had to walk around this wireless mic, and he was handcuffed. If you can imagine putting your hands together closely and sort of like -—

AMY GOODMAN: In front of you.

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

In front of you, like in a prayering position, if you’re praying. And imagine putting on a microphone. It was very difficult. He was handcuffed the whole time.

AMY GOODMAN:

Because he had to do it himself?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

Right. And also, when I’ve seen him at times, he’s also been shackled to his waist. And this is for a completely non-contact visit. Then we taped the commentaries, pieces of paper, because Mumia is not allowed to bring any paper to this interview at all, or a pen. So he has to ship out handwritten copies of these commentaries. We type them up, we bring them back, and we physically have to tape them to the Plexiglas for him to read.

AMY GOODMAN:

You were allowed to bring in a piece of paper?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

Well, for that, because it was a journalistic visit. So, for that instant, we were allowed to bring in both tape recorders, a wireless mic and paper and Scotch tape. So we taped them to the glass, and he read them. Mumia is such an enormously brilliant commentator that he was actually correcting the copy as we were going, so it was a really exciting thing.

The first time I recorded him in 1992, he hadn’t been recorded in ten years. Now, he was a broadcast journalist for WUHY, which is now WHYY, and when I sat down in front of him in 1992, he literally hadn’t recorded in over eleven years. And I’ve done a lot of interviews. I’ve done hundreds and hundreds of interviews for broadcast, and he was the most professional interview I’d ever done. He was quite good, and he loves the environment of recording. And so, any time we go in, he makes a special effort, I think, to really record well.

AMY GOODMAN:

Now, you, personally, did not go in for this last recording in October.

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

I recorded Mumia in three or four sessions over the last couple of years. After National Public Radio, I was banned from the prison for a year, for taking an illegal photograph of the outside of the institution, which it was a just a photo of the institution, and HBO has run hundreds of feet of film of the outside of the institution, but because I put my name on the photo credit of a photo, I was banned for a year. I —

AMY GOODMAN:

Is there a law against taking a picture of the institution?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

I don’t believe there’s any laws against taking an institutional picture. I’m sure they have stock footage of that photo. It was just an attack on me. And we were mobilizing so many different levels of the legal fight that it was very hard to mobilize yet another legal fight. But we have been hiring, like, different sets of lawyers and getting people mobilized to help us gain access. At that moment, we actually waited a year, and I went back in as a social visitor. And in the meantime, I’ve been applying constantly to get back in. So every couple months I apply for another visiting session, and they give me different reasons every single time I go in for why we can’t go in. This last time, it was that I could go in, but I could only bring a paper and a pencil, and that was in July. And we had been fighting that. In the meantime, honestly, we need this tape. So what I did is I contacted an English group, Index on Censorship, had them —

AMY GOODMAN:

Which is a magazine.

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

A magazine — had them assign me the story, and then I hired an engineer and a photographer to go in, because most prisons are parochial, small institutions and little fiefdoms, and so they react differently to requests coming from outside the US. And so, while they were shutting down at least everybody in Pennsylvania and shutting down a lot of people nationally, they didn’t, in this instance, shut down a request from England.

AMY GOODMAN:

And they didn’t know it had anything to do with you?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

No.

AMY GOODMAN:

So, who went in?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

Janice Leber, an engineer form KPFA, and Nolen Edmonston, a photographer, both went in.

AMY GOODMAN:

And what was their visit like?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

It’s a very new high-tech security institution that is all about psychological and physical torture, for both people who visit and people inside. Mumia is locked down, doesn’t see hardly anyone, in solitary confinement twenty-three hours a day, five days a week, and twenty-four hours a day over the weekend. And he has very little contact with other human beings. All the walls are white. It’s like a hospital setting. It’s not an old prison that allows for more people to be around. It’s a pod unit, and so they see very little people. They eat in their cells, they sleep in their cells, they do everything in their cells. It’s quite horrific.

So when people actually go into this prison, they see that medical institution-like place. And Janice was strip-searched, in that she had to remove a lot of her clothing in order to pass the metal detector, and I think that was traumatic, pretty traumatic. And it’s hard also because you’re going down into the deeper recess of this institution, and then you’re able to see Mumia really handcuffed behind the Plexiglas, and that’s quite difficult.

AMY GOODMAN:

And so, once she made it through, was stripped, got dressed again, and saw Mumia, he took the mic, put it on himself and started to record. Were there other people in the room?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

The guards, when Janice first got to the room, said that she couldn’t talk to Mumia unless that woman was present. And they were referring to an administrator. So while they started to chat with Mumia about his current — what is he? He’s getting a Master’s degree, and he’s writing, things like that — they made them stop talking, and they wouldn’t allow the interview to continue unless this woman, the prison administrator, was present. Now, these rooms they are only four by five. So the woman pulled up a chair and sat right at Janice’s elbow through the entire interview.

AMY GOODMAN:

Was she taking notes, the woman?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

Yeah, she was, the entire time. Now, I’m not sure she knew what was happening. I mean, it was scheduled as an interview, and Mumia was reading his commentaries. I’m sure she was affected by his incredible analysis. I would hope so, anyway.

AMY GOODMAN:

Why doesn’t Mumia Abu-Jamal talk about his own case in these commentaries?

NOELLE HANRAHAN:

When I was doing the research for the commentaries, of which ones to pull and record, I had to read 400 commentaries Mumia has written over the last couple years, and he’s mentioned his case twice. I mean, he’s a radio journalist, he’s a reporter, who’s inside, who’s continuing his craft and his profession. And he talks about other people. He has a deep sense of caring of other people’s stories and anecdotes and information, and that’s really what he writes about. It was funny when NPR said we wouldn’t record Mumia talking about his case, because we were laughing because Mumia doesn’t write about his own case. Part of it comes from him being a journalist, and some of it might be his retrospect, in terms of his lawyers talking about his case before he gets a true hearing. His quote is that “I’ll give a description of the events of the night, when I have a fair trial, when I have my resources, and when I have a jury in front of me.” But more than that, Mumia’s been writing for fifteen years now, and he doesn’t mention his case because he really sees it as his craft.

AMY GOODMAN:

Noelle Hanrahan, I want to thank you very much for joining us. Noelle Hanrahan, who’s head of the Prison Radio Project based in San Francisco. And it was the Prison Radio Project that went in, in October, and recorded Mumia Abu-Jamal’s latest commentaries. Again, after that, the prison authorities, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, ruled that all prisoners in the state could no longer be recorded or videotaped.

When we come back, you’ll hear from the spiritual adviser of Mumia Abu-Jamal, who has just come from the prison. Then we’re going to be playing another commentary of Abu-Jamal, and then we’ll be joined by two journalists from the Society for Professional Journalists, who will talk about their campaign around the company to fight administrative restrictions that limit media access to prisoners. And you’ll be hearing from a listener who called in just a few days ago to say he objects to the fact that we are running the commentaries of Mumia Abu-Jamal.

You’re listening to Democracy Now! We’ll be back in sixty seconds.

Media Options