Guests

- Frances Fox Pivenlongtime social movement scholar, and distinguished professor emerita of political science and sociology at the City University of New York Graduate Center.

As the United States heads into another recession and labor organizing is surging, we speak with leading sociologist and longtime social movement scholar Frances Fox Piven as she turns 90 years old. “We’re at another juncture: a bitter contest about democratic rights,” says Piven, who claims the U.S. has always been a “limited democracy.” Despite attacks on fundamental rights, Piven says, “people do have power” to organize and protect their rights, because “we live in a complex, integrated society where the activities of ordinary people really do matter.” Piven’s groundbreaking books include “Regulating the Poor” and “Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail” with her late husband and collaborator Richard Cloward.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

With the midterm elections four weeks away, we spend the rest of the hour with the sociologist, the activist, the legendary Frances Fox Piven. She turned 90 on Monday. Frances Fox Piven is a longtime social movement scholar, distinguished professor emerita of political science and sociology at the City University of New York Graduate Center. Her groundbreaking books include Regulating the Poor and Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail with her late husband and collaborator Richard Cloward. Her other books include Challenging Authority: How Ordinary People Change America and Why Americans Still Don’t Vote: And Why Politicians Want It That Way.

We welcome you back to Democracy Now! Happy birthday, Frances Fox Piven! It’s great to have you with us.

FRANCES FOX PIVEN: Oh, thank you so much. It’s lovely to talk to you again. I’m glad to be on the program.

AMY GOODMAN: So, can you talk about where we are today in this country and movements around the world, from your perspective and your almost a century of wisdom around people’s movements? OK, maybe more like 70 years, but…

FRANCES FOX PIVEN: Well, we’re at a kind of crisis juncture in American development and in the world’s development. But we’ve been there before. Democracy — we think of the United States as a democratic country. It’s always been a very limited democracy. And what kind of — what democratic rights we have have always been fought for. We didn’t get them automatically, and we didn’t get them with the agreement of the propertied classes in the United States. So, American history is punctuated by bitter fights over the contest between a kind of authoritarianism and democracy. And we’re at another juncture of a bitter contest about democratic rights.

And it’s complicated because it isn’t necessarily all the people, the ordinary people, who fight for democracy. People — all sorts of cults have a grip on American development. And the very complexity of our political system makes it more likely that authoritarian — the authoritarian classes who control the American economy will dominate at least parts of the population, parts of the constituency we wish would be democratic.

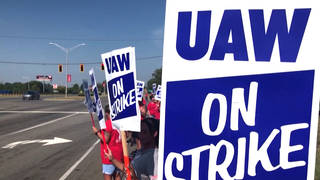

However, always, from the very beginning of the American experiment, always people have discovered sources of power which make it possible to retain some democratic rights and to fight for new democratic rights. That’s, I think, the key point I would like to make: People do have power. And they have power because we live in a complex, integrated society where the activities of ordinary people really do matter. And because they really do matter, because they go to work, because they drive to work, they use the transportation system — because everyone depends on everyone else, people can exercise power. And much of that power is achieved, realized, through a kind of defiance, through a kind of refusal. That’s what a strike is. People withdraw their labor. But they can also withdraw other forms of obedience. And that’s why there is always the prospect that we will survive this assault on democracy, that we will make progress, that we will control environmental pollutants, that we will limit the use of military power. We do. We achieve these things, even though it’s always bitterly contested.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Frances, you mentioned the ability of people to protest. First of all, happy birthday to you!

FRANCES FOX PIVEN: Thank you, Juan.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I wanted to remind you that I remember — I think it was a classic picture, back in — 55 years ago, in 1968, of you climbing up to a second floor — the second floor of a building at Columbia University when we were on strike, coming in to join the protesters. That was 55 years ago. And I’m wondering —

FRANCES FOX PIVEN: And it was the math building.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yes. And I wanted to ask you about the role of these protest movements in effecting social change, whether it’s the student strikes, labor strikes, Occupy Wall Street, in terms of effecting major changes in America policy.

FRANCES FOX PIVEN: Well, I think that movements, protest movements, defiant movements, movements that break the rules, are the main lever, the main weapon, that ordinary people have in realizing their aspirations and protecting their democratic rights. This doesn’t mean that everybody is sort of on track, that every — that the movement includes the entire population. But the abolitionists, for example, or the strike movement of the late 19th, early 20th century, or the civil rights movement, these movements defied the usual norms, protocols of cooperative living in a dense society, and because they did, they shut things down. And because they shut things down, they had to be attended to. Their demands had to be responded to. Their vision of a better society had to acquire a kind of recognition.

So, I don’t think that’s changed. We still live in a densely interdependent society. It is still the case that virtually everybody in the society is locked into cooperative relationships, which make their participation and their acquiescence necessary, so that this kind of mass refusal is still the main lever through which ordinary people change American politics.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: But, Frances, these kinds of protest, resistance and refusal are not a province solely of those who are progressive in the left. We are seeing now in the United States rising populist fascism. And I’m wondering your thoughts about the dangers of the growth of authoritarianism and fascism in the United States.

FRANCES FOX PIVEN: I think it’s extremely dangerous. I think, in fact, that I understand fascism to consist of a kind of coalition between propertied elites and a defiant, discontented, MAGA-like mob. That was German fascism, Italian fascism. Bolsonaro is another example, Duterte. So, it’s complicated. And what we have to worry about is the difficulty of understanding what’s happening in a complicated political system. And because it’s so hard to understand, people are susceptible to propaganda in a way that is very, very dangerous, so that we can have, for example, Trump tell a rally of MAGA adherents that “Aren’t you glad about all the automobile plants I brought back to Michigan?” and no automobile plants were brought back to Michigan. But who knows? It’s hard for people to understand their own environment, their own society.

And that’s why that gives a very important role to activists, to educators, to DSA. So, it’s a dangerous time, but there is no alternative except to try to work with the people and take advantage of the critical role that people play in making our society function, so that the factories hum, the highways move, the subways move. All that depends on cooperation. And our ability to be a truly democratic society depends on the ability of people to withdraw that cooperation.

AMY GOODMAN: Frances, I’m wondering your thoughts on Ben Bernanke winning the Nobel Prize for Economics. He was the Fed chair from 2006 to 2014, appointed by both Bush and Obama, and then he made his way through the revolving door, senior adviser to Citadel, one of the country’s largest hedge funds. But that kind of approach to economics? And contrast that, for example, with a woman you have worked with for so many decades, who we just lost, Barbara Ehrenreich.

FRANCES FOX PIVEN: Barbara was a wonderful, brilliant person. I’ve known Barbara for more than about 50 years. And I worked with her. I wrote with her. I loved her. She had — she was not only very smart, she was the essence of a decent person, and a woman of the left. So, her loss is tragic, but inevitable, because we all die. And Barbara leaves in her — Barbara’s death leaves us with her accomplishments, not only her books but her Economic Hardship [Reporting] Project, in which she actually paid for young people to — young and poor people to become the authors of their own life, to begin to affect journalism and produce the journalism that will give us knowledge of what it means to be poor in the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: And Ben Bernanke?

FRANCES FOX PIVEN: I have no opinion about him. I mean, he’s a member of the economic elite. He is as the economics profession in general is. He is the articulator and the justifier of oligarchy, of an economic oligarchy, which is what the United States is.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Frances, we only have about a minute left. I wanted to ask you about voting. Several of the books that you and Richard Cloward wrote were credited with pushing the motor voter rule, making it easier for people to register to vote. Your response to how you’re seeing the attempts to restrict voting as much as possible across the United States by conservative Republicans?

FRANCES FOX PIVEN: Well, it’s very obvious — isn’t it? — that Republicans don’t think they can win elections if they follow the basic rules of a democracy, if they count the votes, if they allow people to vote, and then they count the vote. So, observing that they’re not likely to win if they do that, they’ve decided that they’re going to tear down the elemental democratic arrangements that we have in the United States. It is so horrifying, and so important that we rally to defend basic democratic rights. It’s not that these always work. It’s not that they’re perfect. It’s not that they aren’t corrupted. They are all those things. Nevertheless, they help to humanize American society. It is a good thing that people vote. And more and more people actually do vote. And that’s good, but we have to protect it, because there is actually a concerted effort to dismantle democracy. Republicans and the propertied classes —

AMY GOODMAN: We have 10 seconds.

FRANCES FOX PIVEN: — have perceived that they’re no longer popular. And because they’re no longer popular, they’re going to smash the arrangements through which people express themselves in the American political system and have some influence.

AMY GOODMAN: Frances Fox Piven, we thank you so much for being with us, longtime social movement scholar, distinguished professor emerita of political science and sociology at CUNY Grad Center. Again, a very happy 90th birthday!

That does it for our show. We have two full-time job openings. Check democracynow.org.

Media Options