Guests

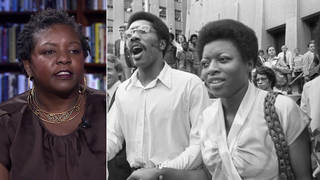

- Cyntoia Brown-Longauthor of Free Cyntoia: My Search for Redemption in the American Prison System.

At the age of 16, she was arrested for killing a man who had picked her up for sex, after she had been forced into sexual slavery as a child. She was tried as an adult and sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of first-degree murder for shooting the man who bought her for sex when she feared for her life. Today Cyntoia Brown-Long joins us to share her experience, what has happened in the 15 years she was incarcerated, and how she won her release. In an incredible development, after a years-long campaign to win her freedom, Cyntoia was granted clemency in January after former Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam commuted her sentence. She was released from prison in August. We spend the hour discussing her experience as she recounts in her memoir, published this week, “Free Cyntoia: My Search for Redemption in the American Prison System.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: At the age of 16, she was arrested for killing a man who had picked her up for sex after she had been forced into sexual slavery as a child. She was sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of first-degree murder for shooting her rapist. Today Cyntoia Brown-Long joins us to share her experience, what’s happened in the 15 years since she was incarcerated, and how she won her release.

In an incredible development, Cyntoia was granted clemency in January, after former Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam commuted her sentence for murdering 43-year-old Johnny Allen, an estate agent who took her to his home for sex in 2004. Cyntoia says Allen was behaving erratically and owned a number of guns, and that she feared for her life when she shot him in the head and made her escape. At the time, she was being sexually trafficked and repeatedly abused and drugged and forced into prostitution by a pimp nicknamed “Kutthroat.”

She was just 16 years old at the time of the shooting, but she was tried as an adult and convicted of first-degree murder and aggravated robbery in 2006 without the possibility for parole until 2055. Juveniles in Tennessee who are sentenced to life in prison must spend at least 51 years behind bars. Cyntoia’s case drew widespread attention on social media under the hashtag #FreeCyntoiaBrown. Pop superstar Rihanna wrote, “Something is horribly wrong when the system enables these rapists and the victim is thrown away for life!” After her repeated appeals in the case were denied, Cyntoia spoke at her clemency hearing in January.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: I can’t make up for what I did, but they’ve given me a chance to do so much more, you know. I’ve been able to help people, which is amazing. Young people, young kids. They listen. …

And I’m still going to try to help people. I still am, because it’s something that people need to understand. It’s something people need to know. There are so many things that I understand now that I didn’t know. And there are so many young people that still don’t know. And I feel called to share that.

And whatever you decide, I respect it, but, I mean, I do pray that you show me mercy and that you give me a second chance. That is my prayer. And I can assure each and every one of you that if you do, like, I won’t disappoint you. I’m not going to let you down.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Cyntoia Brown-Long speaking in January. She was ultimately granted clemency and released from prison in August. She is now 31 years old. This week, she published a book about her experience. She’s doing her first interviews. Her memoir is titled Free Cyntoia: My Search for Redemption in the American Prison System.

Cyntoia Brown-Long, welcome to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: So you are sentenced to life in prison at the age of 16 years old. If you would go back in time and tell us what happened on the night of August 7th, 2004, what led to, well, everything that has happened now, although there was so much before it?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, on the night of August 7th, I was involved with a man by the name of Kutthroat, as you mentioned, and I was going out meeting with men, having sex for money. And one of the men that had picked me up was a 43-year-old man, as you said, a real estate agent. And he took me back to his home, just started acting really, like, strange. I started to feel like I was in a situation that I just couldn’t get out of, although I just kind of just wanted to just leave, felt very uncomfortable. Was showing off his guns, things like that. Things just really escalated, and it came to a point where I shot him. I felt that something was about to happen to me. I left, went back to the room.

AMY GOODMAN: Got in his pickup truck.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Right, got in his pickup truck — that was the only way I could go back — and went back to the hotel room that I had shared with Kutthroat. About within 24 hours, the police had come and arrested me. I spoke with them freely. I felt that, you know, I had defended myself, so I didn’t have anything to hide. Next thing I know, I’m being charged with criminal homicide. So…

AMY GOODMAN: How much can you understand as a — at the time, you were 16?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Right, at the time, I was 16. I really didn’t understand the gravity of the situation that I was in, the situation that led to me being arrested. And then, of course, the entire arrest process, the charging process, I didn’t get it. And whenever the detective had spoken with me before I went into the confession room, you know, he kind of just said, “Talking to me is going to be the difference between nine years and 99 years.” So, choice to me was obvious.

AMY GOODMAN: No lawyer with you.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Right, no lawyer, no parent. At the time, I did tell them that I was 19, because that’s what Kut had told me to say if the police ever got me. You know, couldn’t tell them I was 16. However, they did find out, after the fact, that I was 16 years old. Still didn’t attempt to try to call my parents, try to call a lawyer, anything like that.

AMY GOODMAN: Take us back, because you’re referring to Kutthroat, a man you’ve come to see in a very different way than you did as a child.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: Even though what happened that night leads to your sentence of life in prison, I want you to go back in your own life now and tell us about where you were born and what led you to the point you were on that fateful night.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, I was born on Fort Campbell — it’s a military base — raised in a military community, very supportive community. My family was very supportive. My mother is a teacher. My father, he’s retired military. Had pretty much everything that I needed as a child. But, you know, I would go to school, and other kids started pointing out that I was different from my parents. I was different from other people, didn’t really feel like I fit in anywhere, was kind of treated as an outcast and started to develop behavior problems, attitude problems. The school labeled me as “the bad kid.” Started finding out that teachers wanted to just get rid of me. They would put me in ISS for the littlest of things, little smart remarks that just natural for certain kids. Found myself in alternative school, around the wrong crowd. You know, alternative schools are pretty much like schools’ version of prison. You know, it’s just somewhere to just toss kids.

AMY GOODMAN: In sixth grade, you were tossed out of school?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Right, right, sixth grade. So, started getting in deeper with different things, started skipping school, actually wound up catching my first charge with some of the other kids that I had met at alternative school. And then I entered into the juvenile justice system. So, pretty much downhill from the time that I entered alternative school. From juvenile justice system, I started running from state custody, from the facilities that they had placed me in. And I started staying on the streets in Nashville. And I was on the streets in Nashville with the people that I had met from running away, whenever I was introduced to Kut.

AMY GOODMAN: And explain who Kutthroat was.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, Kutthroat, he — I had known him just for a few weeks, just for a few weeks. And I had met him right after I had been raped for the first time. Lot was going on. And I had always wanted acceptance from other people. I had always wanted to be seen as though I belonged somewhere. And so it was rather quickly that I found myself just drawn to him. I felt that, you know, he listened to me in ways that no one else listened to me. I really felt in my head that I was in a relationship with this man. And so, when it came time for him to say, “We need money for this, we need money for a hotel, and this is what you can do,” it was like, “OK, I’m going to do this, because I love this person, and I’m just contributing to the relationship” — completely unhealthy thought patterns that I had developed from actually being on the run, learning unhealthy behaviors, unhealthy understanding of sexual relationships. I really had come to see my body as, you know, a good, to be traded for shelter, for food, for money, for the things that I needed to get by. So, with all those seeds that were already planted, it was — his work was, you know, already done.

AMY GOODMAN: He drew a gun on you.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: He strangled you.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, it didn’t start out that way, naturally. I don’t know many people that would stay in a situation where it starts out that way. Of course, they always start out nice, very charming. And, you know, then it would lead to — he would just snatch me up a little, just shake me up, guns with lectures. And when I say “lectures,” I mean like hours on end spent telling me, you know, “You’re nothing but a slut. No one will ever want you but me.” And, you know, in my mind, I was like, “This is not true.” But you’ve got to think like how that’s really just sinking into me. I was already in a low place.

And, you know, there was times that — one time he actually had choked me until I passed out. Like, the man could have really killed me. That was actually on the night right before I had met Mr. Allen, the man that I had ended up shooting. I had really come to expect violence from men. And I really think that that played a big role in what happened that night. And it would take years for me to really just unpack everything, to just really process all the trauma that I had really built up.

AMY GOODMAN: When did you come to understand you had been placed in the foster care system as an infant?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, I was never placed in the foster care system. I was actually adopted directly from my biological mother. So she had actually asked the family that I was with to take care of me. She was incarcerated. She was in and out of jail. And they adopted me directly from her, so I was never placed in foster care.

AMY GOODMAN: And when did they explain that — your parents, explain that to you?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, I found that out, I guess I was like 5, whenever I had started school. And, you know, I was in the classroom. Your parents bring you to school because it’s the first day of class. And as the teacher is talking with my mom and dad, I’m playing with the other kids, and I can remember one of the other little boys, he had asked me, you know, why don’t I look like my parents. My mother has dark skin; my father, as well. And, you know, I had never really thought about it. I didn’t feel any different. Mommy and Poppy, they had never treated me any different, so there was no reason for me to like really know that I was different. And one question led to other questions to a full-blown interrogation from kids. That’s just what they do. You know, one answer is never good enough.

So, I remember getting in the car with my mother after class, and, you know, I asked her. And she explained to me that I was mixed and that I was adopted. And there was — introduced this idea of this mystery woman that I came from. And that kind of just set up this lens for me where I just started feeling like, “Oh, well, I really don’t fit here, do I? And I don’t fit here, either.” And so, it was just a seed that had been planted.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain the moment when you were in one facility or school, and your parents couldn’t come to pick you up, so they sent a family friend who had been sexually abusing you.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Well, he hadn’t been sexually abusing me; he had made an inappropriate comment. So, I was actually — I had come back from court, from the facility. The court didn’t tell my parents that I was having court that day. They just brought me up from the detention center, and they were going to release me. Well, my mother, she was at work, and she couldn’t just leave. She didn’t have a substitute. She called my father. My father had already left. He was driving trucks at the time. And he had called his friend to come pick me up. And this —

AMY GOODMAN: How old were you?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: I was 12? Twelve, about to be 13, or maybe I was 13, somewhere in there. I think it was 13, actually. So, I think that happened in March. So, 13 years old. And he had called this friend to pick me up. This friend, I was previously on a trip with him, whenever my parents had gone out of town for their anniversary. And the people that we were with had sent me out to go tell him to come inside, to come into the cabin, because dinner was ready. And whenever I went out, he was sitting in his truck with his leg hanging out, door open. He was on the phone with someone. And whenever I said, “Hey, it’s time to eat,” he had spoken to the person on the phone. He was like, “Yeah, it’s my homeboy’s daughter. She’s one of those girls that’s developed in all the right places.”

And, you know, I have been raised on Lifetime movies, so I knew, like, there are certain trigger words that were just not OK. You know, my mother made sure that I understood that. And so, you know, I slammed the door on his leg. I ran inside, and I told the group that I was with, you know, what had happened. And I’m expecting like, you know, they’re finna go in on this man, like this is not OK. But the reaction that I got was, he walks in, and they just hand him a plate of steak, and everybody just sits and talks normally. And so, it was like, “Wait a minute. Like, you know, Mom always told me that I needed to tell someone, I needed to speak up about things. And I do it, and nothing happens.”

So, fast-forward all these months later, and he comes to court to pick me up. Well, when I tell the woman at court, the clerk, “I’m not going with him. I don’t feel comfortable leaving with him, being alone with this man,” she tells the judge, and the judge says, “Fine. We’ll put you in state custody.” And state custody is the worst fear of every kid who’s been involved in the juvenile justice system, because it’s the most severe punishment they can give you. For me, being 13 years old, that meant that they can hold me up until I was 19 years old, because it’s an indeterminate sentence. And so, it’s like, “Wait, like, I’m being punished now? Like, I was going to get to go home, but because I don’t feel comfortable around this man and I spoke up about it, now I can’t go home?” So, definitely — definitely wasn’t healthy. Definitely didn’t teach me that, you know, it was a good thing to speak up for myself, it was a good thing to advocate for myself. Taught me the exact opposite.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to break and then come back to our discussion. We’re talking to Cyntoia Brown-Long. She’s a sex trafficking survivor who was sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of first-degree murder. In January of this year, the former Tennessee governor granted her clemency, and she’s just gotten out of prison. This is one of her first post-prison interviews. We’ll continue with her, learn what happened at her first trial and then beyond, and how a child gets sentenced as an adult. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Stronger” by Mary J. Blige. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. We’re talking to Cyntoia Brown — well, now Cyntoia Brown-Long, who is a sex trafficking survivor, sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of first-degree murder for shooting her rapist as a teenager. She had been sexually trafficked and repeatedly abused and drugged. The shooting happened when Cyntoia was 16 years old, but she was tried as an adult. Cyntoia was granted clemency by former Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam in January. She was released from prison this past August. She is now 31 years old, out with her memoir, Free Cyntoia: My Search for Redemption in the American Prison System.

So, let’s take it to your arrest within 24 hours after you murdered the man who took you home. You were terrified by him. He was going to give you money for sex. You’re a teenager. He’s showing you his guns. You shoot him. You leave. The police get you. You have no lawyer. And talk about what happened in your hearing, your — explain what a transfer hearing is — and then, ultimately, what happened in your trial, how you ended up with life in prison.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, shortly after my arrest, I was assigned a public defender. And that public defender was part of the juvenile court, so it was her job to prepare my case for a transfer hearing, because the district attorney had actually asked the court to try me as an adult. And so, what they do is they actually — number one, they find if there’s probable cause to believe that you actually committed the offense. And then the second part of the hearing is determining whether there are actually resources within the juvenile justice system that they can use to treat you, because the goal of the juvenile justice system is supposed to be to remove the taint of criminality. Their focus is supposed to be rehabilitating any individual that comes into the court. So, at the transfer hearing, I testified. I was still transferred. I was tried as an adult. They figured that there was just not enough time left within the juvenile court jurisdiction, which was three years — two-and-a-half years, for them to help me. So, I go to the adult jail, to the county jail, housed in a cell by myself, solitary confinement, to be kept away from the adults.

AMY GOODMAN: How long are you in solitary confinement?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Two years. So, from the time I was 16 until I turned18, I was in solitary confinement.

AMY GOODMAN: What was that experience like? What does it mean to be in solitary confinement? How large was your cell? Who were you allowed to see?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Yeah, I mean, it was horrible. It was — it was horrible. You know, the cell is about the size of probably your bathroom at your house. And you don’t get out much. You get out for an hour a day, if they remember you, where you can go outside to be locked in a kennel, which — pretty much a dog kennel. It’s a cage, a fenced-in cage. And then they’ll take you to the shower. And, you know, it was really hard, especially with everything that I was dealing with, because you had like nothing to distract you. You had nothing but everything that you were facing, all the anxiety, all the thoughts, all the trauma. Everything that you’re trying to deal with is just there in that room with you. And —

AMY GOODMAN: This is before the trial?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: This is before the trial. This is while I’m awaiting the trial.

AMY GOODMAN: Solitary confinement — you’re a teenager — for two years.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: For two years, yes. For two years, because every juvenile at that time had to be in solitary confinement. That’s just how they did. I mean, they didn’t have to be. There was, you know, juvenile facilities that could have housed them until they were 18, but that’s just what they felt, I guess, was more convenient for them. So, housed in juvenile — I mean, housed in solitary confinement as a juvenile, spent all that time — mental health constantly, just feeding you different medications, because when you’re telling them, you know, “I’m feeling this, I’m experiencing this,” they just find another pill. You know, they just kind of use you as a guinea pig. So…

AMY GOODMAN: So you’re drugged through this time, in a different way than when you were on the streets.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Absolutely, absolutely, the entire time. So, I finally make it to trial, and I was convicted. I was convicted on all counts.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you testify in your trial?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: I did not. I had wanted to testify, but my attorneys had advised me against it, because they felt that my earlier statement in juvenile court could have been used to impeach me, because it was different from when I was telling the police that Kut had nothing to do with anything, I didn’t even know him, I had just met him. So, they said that by me having testified the way I did in the juvenile court, they could have used that to impeach me. Come to find out later that they never could have used that to impeach me anyway, because anything said at the juvenile transfer hearing can’t be used against you in later proceedings. So my attorneys were mistaken, you know, with that.

AMY GOODMAN: A rather major mistake to have made.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: It was.

AMY GOODMAN: And also talk about how your view of Kut, Kutthroat, changed, how you came to understand what sex trafficking was.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, my view of Kut himself, like, that took time to change, because whenever I was first incarcerated, I was still thinking, like, “This is my boyfriend. I know what my attorney is telling me, that he’s making statements against me to the police, but I don’t believe him, because he told me not to believe it. He told me ahead of time that they would tell me these things.” And, you know, I was just so loyal. But he didn’t deserve it at all. But I was just so loyal to him.

And it took for them to actually sit down with me. One of the women who actually worked in the juvenile court office, the defender’s office, had told me, you know, “You’re facing life.” And I’m like, “Wait. What do you mean I’m facing life?” Like, I didn’t even know that was a possibility for me at the age of 16. And so, my other attorney had sat down with me, and she took a piece of paper, and she divided it into four sections. And she was like, “Let’s really think this through.” And she titled the sections “Things Kut Does That Make Me Feel Good,” “Things Kut Does to Make Me Feel Bad,” Good Things About Kut,” “Bad Things About Kut.” And, you know, I got to see, putting it on that paper, that, you know, the bad far outweighed the good.

AMY GOODMAN: This is the man who held guns to you, who strangled you.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Right, right. So, actually getting to see, like, that forced me to like really rethink things. And it’s like, “This isn’t what I thought it was.” And, you know, they let me know, like, “It’s important for you to tell the court everything. Like, you’re facing serious charges here. You’re facing life in prison.” And so, you know, when I went to the juvenile court, I was like, I’m going to have to tell them everything. And I did, at the transfer hearing.

AMY GOODMAN: At the transfer hearing.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: But when it came to your trial, they said you could not speak.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Right. When it came to the trial, they advised me not to testify. I wanted to testify. My family wanted me to testify. But they said that it wouldn’t be in my best interest. And so I didn’t. They never got to hear my side of the story.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the day you were convicted. Describe where you were in court, what happened and when you were sentenced to life in prison.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, the day that I was convicted, this was — I believe it was the fifth day of trial. And —

AMY GOODMAN: You had never spoken.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: I had never spoken, just sat there in the courtroom, showing up every day, just listening. And, you know, you’re listening to everybody just talk about the worst thing that you’ve ever done, and paint you in the worst possible light. It’s brutal. It’s really brutal. And you can’t even speak up for yourself. Like, you’re having to depend on other people to speak up for you, but there’s never going to be anyone that advocates for you the way that you can. And so, it’s really difficult. And at the conclusion of the trial, the jury goes for deliberation. I sat in the holding cell for a while.

AMY GOODMAN: Had they brought up your age in trial?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: They did. They brought up my age. You know, my attorneys had brought up the fact that I was with this man that was abusing me. They had brought up the fact that, you know, there was actual photo evidence where this man was taking nude pictures of me. And I can remember, you know, when my attorney had taken the picture, it was folded up. He didn’t show me nude, but he just showed the look on my face, just how miserable I was, just how blank I was, to the jury. And the district attorney comes back —

AMY GOODMAN: They show a nude picture of you at trial?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Right. My attorney didn’t show the nude part. He had blocked it off; it was folded in half. However, the DA actually came and unfolded and was like, “Well, this is the rest of the picture.” And I was like, “Like, what was that about?” My attorneys and I, like, we were all shocked. You know, so it was just — that is just one moment that just indicates how it was just like one big just assault on everything that I felt about myself. Like, it just made me feel horrible. It made me feel like a horrible human being. It made me feel, you know, this is my fault, like what happened with me with Kut. Like, I didn’t ask for him to do those things to me, but I was made to feel that I did ask for it.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you’re in a holding area, and then you’re brought in for the verdict.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, I’m in the holding area, and they tell me, actually, that because it was taking so long, it was getting so late, they actually thought that deliberations would pick up that Monday. So, I’m thinking, “OK, this is good,” because they say the longer they deliberate, the better it is. “Like, this is good. Like, surely, I’ll get 15 years for second-degree murder, worst-case scenario. Like, surely, they won’t find me guilty of first-degree. Like, it’s just not what happened.” You know, you keep thinking, “Like, I know what happened. Like, it’s not what happened. Surely, they won’t find that.” And so, my mother had left, because they told her they won’t come back with a verdict today. And so my mother had left. And I’m there by myself, with my attorneys.

When they call, they say, “Oh, they came up with a verdict.” And I was like, “They did?” And we go up there. They bring the jury in. And I’m just looking at them, just desperate to get any kind of indication of what happened. And I remember there was one man, it was a black man, and during jury questioning, they had asked him if he had any experience with the justice system, any kind of thing that would make him, you know, biased. And he had said that he had a nephew that was actually involved in the system. And so, I’m thinking, “OK, he’s going to fight for me, like, because he understands.” But whenever he came in, like, he looked at me, and he just hung his head and shook his head. And I was like, “That’s not good.” And so I kind of knew then, you know. And I looked at every single one of their faces, and they wouldn’t look at me. They wouldn’t look at me. And I was like, “This is not good.” And so, whenever they read the verdict, it was like — like you could just feel this, like it just stabbed you in the heart, like each word. And, I mean, it was rough. Then, right after that, the jury said — I mean, the judge says, you know, it’s an automatic life sentence. And you’re just stuck there, like, “What just happened?” You know?

AMY GOODMAN: So, it’s automatic life sentence. You were sentenced that day to life in prison.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Life in prison. In the state of Tennessee, anytime you’re convicted of first-degree murder, it’s automatic life sentence. It doesn’t matter if you’re a juvenile. No consideration is given to any mitigating factors. There’s absolutely no way around that. It’s automatic life sentence, mandatory.

AMY GOODMAN: So, let’s talk about what happened to you then in prison. You’re in an adult prison. You’re 16 years old. You face life in prison. You have to serve over half a century of that. Talk about your feelings of, I guess you could say, redemption. I mean, the subtitle of Free Cyntoia, your memoir, is My Search for Redemption in the American Prison System. Talk about the educational system in the prison and who you came to meet.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, my entire life, I could remember always feeling like I was thrown away, like I wasn’t worth salvaging, you know. And, of course, the entire court process, it just reinforced that belief. So, naturally, like, the way I felt about myself, like, it was just at an all-time low.

And there was a program, a volunteer program from a local university, Lipscomb University in Nashville, that had come, and they offered college courses, free of charge, for people housed at Tennessee Prison for Women. And took some time, took some work, and I finally got into the program. And once I get into this program, you know, I start thinking, like, “Wow! Like, I can actually do these things. I’m actually smart.” Like, you start to think about, you know, “These people are actually listening to what I’m saying, and they think I’m smart, and they don’t think that I’m some dumb girl who made all these dumb choices. They see me as so much more than that. They don’t even look at the worst thing that I’ve done. Like, they don’t even acknowledge that. They worry about who I am now, and they see me for me.”

And I can’t tell you just how redeeming that is. And it just made me — it made me want to do better. It made me want to live. It made me want to strive. And it was just an incredible experience. And it just like really just set me on a path. Didn’t take me all the way there. You know, I wouldn’t come all the way to feeling that, you know, I’m fully walking in my redemption until I developed a relationship with Jesus. And, you know, I talk all about that in the book, and, like, what an important, important part that played in my life and in my freedom.

AMY GOODMAN: You also talk about a mentor you had when you were in prison. How did you meet her?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Are you talking about Mrs. Seabrooks?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Yeah, so, I met Mrs. Seabrooks when I was trying to get into the Lipscomb program. She’s actually — well, she was; she’s retired now, which is unfortunate, because she was awesome. She was the principal of the education department. And she had given me a chance, and she really worked with me, because there were so many people trying to get into the program, but she had seen, from placement testing, that I had potential. And even though I was on close security, which is a higher security designation, because I had gotten in trouble, she worked with me. And she gave me the chance to interview, to take the test. And then, the day I got off of close security, she allowed me to enter the program.

AMY GOODMAN: When you learned what happened to Kut, in prison — what happened to him?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, I actually learned that prior to my trial. Eight months after I was incarcerated, at the end of March 2005, he was actually killed by another man in a parking lot.

AMY GOODMAN: Did that change your view of having to defend him?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: No. Like, I had already — before that, before he had died, I had already come forward with everything, with the truth. You know, I had told them at the transfer hearing, which was in November of 2004. It didn’t change anything. Even though the detectives had found that information out, they still didn’t follow up on anything. But I thought that I had come to a point where, you know, I was over it, I understood things. But I remember, like, when I found out he died, like, it brought up those old feelings, and I was devastated. I remember just screaming when I found out.

AMY GOODMAN: When you were — when you went to school and you started to really talk and think through things, you started to come to understand the situation you were in, the whole idea of sex trafficking. You had appealed your sentence, and you had appealed — entered an appeal in your case. Talk about when it was denied, where you were, and why it is you never gave up hope.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, I actually lost not just one appeal, but three appeals. My first appeal, my direct appeal, was denied around 2009. Then I filed a postconviction appeal. That was denied, as well. And my final appeal that was due to me was the federal habeas corpus, and that was denied. And it was said that I couldn’t even appeal that. And so, you keep trying, and you keep hoping that some court is going to give me some kind of leniency, they’re going to show me some kind of compassion, they’re going to see all these things. But it never happens.

AMY GOODMAN: So, we have to break, but when we come back, I want to ask you about the remarkable story of your professor at Lipscomb who was the assistant attorney general — you did not realize at the time —

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: No.

AMY GOODMAN: — who had denied your appeal, and the conversation that you had. We’ll be back in a minute with Cyntoia Brown-Long, a sex trafficking survivor who just got out of prison. Her sentence — she was granted clemency by the former Tennessee governor. She had been sentenced to life in prison at 16. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Every Woman” by Vagabon. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. We’re spending the hour with Cyntoia Brown-Long, a sex trafficking survivor sentenced to life in prison at the age of 16. It would be — she would be granted clemency last January by the former Tennessee governor. Cyntoia, you’re in prison. Your appeal is denied. But you’re going to school, Lipscomb University, within the prison. It’s a program that absolutely saved your life.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: It didn’t save my life, but it helped.

AMY GOODMAN: When do you realize that Preston Shipp, your professor at Lipscomb, was the assistant attorney general who denied your first appeal?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, it was at the end of the semester. My appeal had actually came down. It was denied. I had just — that was on a Thursday, that I got my appeal. And the Wednesday night before that, I had had class with him, and he was acting really weird, really concerned, and asked me, was I OK. And I said, “Yeah.” And I didn’t even know why he was asking me that way. And so, the next day I got my appeal as denied. Didn’t really look through it that day. Actually went to a Lipscomb function that night for their literary journal, looking for him for help with the appeal, because I hadn’t read it to even see, but he didn’t even show up that night. He wasn’t there.

And so, that next day, when I went to the law library, my friend Erika East had helped me, you know, to really stop, slow down: “Let’s read it and figure out where we go from here.” And the first few lines, they actually list the parties involved in the appeal, list me, my attorneys’ names, then it lists the prosecutors. And there was Preston’s name. And it was like, “What?” Because the thing is, you see your DA at trial, but when it comes to the appellate court, that’s an entirely different office. That’s the Attorney General’s Office. You never see them because you don’t actually go to the appellate courts to attend those hearings. So I wouldn’t have recognized him, because I’ve never seen him. And for him, he didn’t recognize it, either. It’s very hard, you know, to remember a name in a case. And I think that’s a big problem with the system now. We’re just reduced to case numbers and names on a file. But he didn’t realize it, either. But whenever he put it together, I mean, he was devastated. He felt horrible.

AMY GOODMAN: So you talk with him about your case. He’s the one who denied the appeal.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Well, he didn’t deny the appeal; the judge denied the appeal. But he fought for that. He fought and argued against me.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did he say he understood in speaking to you, that he hadn’t understood when he looked at your case?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Well, he told me like how he didn’t understand everything else that had happened. He didn’t understand — he didn’t know anything about Kut. He didn’t know anything about everything surrounding just that one moment. And, you know, he spoke to me about how him as a prosecutor, how he saw that that was an issue, because, as a prosecutor, you’re just given these certain facts, and you just stand on those facts. You don’t listen to anything else.

AMY GOODMAN: You were granted clemency by the former Texas governor, but it didn’t happen out of the blue. Talk about the campaign that went viral for your release. I mean, the title of your book is Free Cyntoia.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, former Tennessee Governor Bill Haslam granted me clemency January 2019. And I remember filing — I believe it was December 2017 — for clemency. And we had been working with his office. We had been working with some other strategists to prepare a clemency petition for me prior to that. And about a few weeks before we were going to file, a news story had run about me running for clemency, about me filing for clemency. And overnight, it just — it blew up. It spread like wildfire. And it’s really nothing short of a miracle, you know, from God, the way that so many people around the world were just rallying for me to be freed. And it took a year and one month, from the time that I filed the petition, for Governor Haslam to grant me clemency on the basis of all the changes that I had made, the work that I had done with Lipscomb.

AMY GOODMAN: So, superstar Rihanna, for example, wrote, “Something is horribly wrong when the system enables these rapists and the victim is thrown away for life!” What did that mean to you?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: I mean, it just — I mean, that validates everything that I know. Like, there is something wrong when you throw away anybody, when you see people as disposable, when you don’t see that this person is just as capable of being redeemed as anyone else.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to the statement by then-Governor of Tennessee Bill Haslam, who granted you clemency. He said a life sentence without the possibility of parole until you’re in your sixties was, quote, “too harsh, especially in light of the extraordinary steps Ms. Brown has taken to rebuild her life.” He added, quote, “Transformation should be accompanied by hope.” Did you get to meet Governor Haslam?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: I did. And he is just an incredible man, just such a strong man of God, just very humble, very kind, you know, very intelligent. Just it was really nice to meet him.

AMY GOODMAN: Cyntoia, you got married in prison.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: I did.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about what happened. How did you meet Jaime?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Well, I tell you, God brought me the perfect man. Just even the way that we met, which, you know, I detail it further in the book — the way that we met is just — you know, it’s just full of God. You can just see his hand all in it. For about three years — it’ll be three years in January — from the time that we actually met, we started communicating. And we’ll be married in a year, come January.

AMY GOODMAN: He wrote you a letter?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: He did.

AMY GOODMAN: In prison.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: He wrote to me. We started writing back and forth, started spending hours on the phone. He would visit me in prison and was just really there for me, was the person that helped me get through like some of those really, really hard moments. Like, he was there and just is my best friend. I love him.

AMY GOODMAN: And he’s standing right outside this door right now.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: He is. He’s always with me, everywhere I go.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, as we just have a minute to go, the other Cyntoias that are out there. Of course, you are unique, but what you left behind and the people you left behind and what you’re doing now about them?

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: So, I just — whenever everyone was speaking up for me, like, you know, it gave me hope that, OK, we’re seen, like somebody sees us, because you always feel that your voice doesn’t matter, which, you know, that shouldn’t be how it is. And their voice, their situation, their lives are just as valuable as mine. And I feel that God has given me this opportunity to just really use this platform in a way that sheds light on them, as well. Like, there are so many other people like me. There are so many women, so many men, who are facing injustice.

AMY GOODMAN: I saw you nodding your head as I was presenting headlines about Rikers being shut down, and those who are saying it’s not about other jails being built, that the money has to go into education, has to go into programs for people who are imprisoned, particularly youth.

CYNTOIA BROWN-LONG: Right. You know, it’s unfortunate that the first response is to just lock people up and throw them away, when, you know, if you really just take the time to invest in people — like, people aren’t disposable. Like, we’re all capable of redemption. We’re all capable of being helped and being our better selves. Like, everyone deserves a second chance.

AMY GOODMAN: On that note, I want to thank you so much for being with us, Cyntoia Brown-Long, sex trafficking survivor, sentenced to life in prison after being convicted of first-degree murder for shooting her rapist as a teenager. A years-long campaign helped her to win her freedom. She was granted clemency in January, released in August. Her memoir, Free Cyntoia: My Search for Redemption in the American Prison System, it was published this week. That does it for our show. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options